A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — 1979 — World of Krypton 1

In which I discuss Superman: The Movie, the gullibility of children and rocketry ineptitude.

Written by Paul Kupperberg

Pencils by Howard Chaykin

Cover date: July 1979

Warning: spoilers for the issue follow

Children will believe almost anything you tell them. To be fair to those gullible tiny people, they more or less have to. New pieces of information are thrust at them all the time. Heck, most of their waking hours are spent bracing themselves for a fresh barrage of previously unrevealed knowledge. If they were to question everything, they’d barely have time to learn anything.

But it’s not just a matter of optimal time management. Questioning new information also requires an established understanding of how the world works. And children rarely have that established understanding. Mostly because they’re yet to acquire the critical mass of data necessary to build such a framework.

Adults, in contrast, have usually taken in enough information in their lives to develop a worldview that makes sense to them. As a result, if an adult receives fresh information that conflicts with that worldview, then they’ll question it.

Doubts will emerge. Scepticism may well be employed. Incredulity will be a common fallback position.

So when Superman: The Movie was released in 1978, along with the tagline that ‘You’ll believe a man can fly’, that promise wasn’t intended for children. Children were always going to believe Superman could fly.

No, the tagline promise was aimed at adults. And the miracle of that movie is that the promise held true. (The film didn’t promise that we’d also believe that Superman could plausibly pass himself off as Clark Kent. But thanks to Christopher Reeve’s chameleonic performance, everybody believed that too. A bonus miracle.)

The reason that tagline fits so well with Superman: The Movie is because it’s very much not a movie designed for children. The cinematic release is almost two and a half hours long, and we don’t even get a glimpse of the red and blue suit until 48 minutes in. The thrilling helicopter rescue of Lois — the first time Superman actually springs into action — is 68 minutes into the movie.

Now, of course, that initial appearance is worth the wait. Margot Kidder’s “You’ve got me? Who’s got you?” is one of the all-time great movie lines and if you don’t feel like cheering along with the bystanders as Superman catches both a plummeting Lois and an equi-plummeting helicopter, flashing a winning smile while John Williams’ score soars in triumph, then maybe stories about superheroes aren’t for you. But if you’re a child, the more than an hour of Krypton and Smallville table-setting that leads up to that exhilarating moment is a long amount of Superman-less time to sit through.

This, however, was not my concern going into the movie when I first saw it. (I don’t remember exactly when I first saw the movie, but living in a small country town in Australia, it wouldn’t have been until sometime in 1979.)

I would have been either seven or eight years old when I first saw Superman: The Movie. But I had already read a good amount of Superman comic books. I knew my lore. And when I asked my cousin who had already seen the movie how much Superboy was in it, he’d replied with a disappointing ‘none’.

Now, this was concerning. Superboy was my favourite version of Superman. The adventures of Superman when he was a boy spoke to me. After all, I was a boy. Sure, I didn’t have superpowers bestowed upon me by Earth’s weaker gravity and yellow sun. Nor did I have a best friend destined to lose his hair in a chemical accident and grow up to be my arch-nemesis. But I did have loving parents, and a dog (although, again, not a superpowered one). I lived in a small town, went to school and dealt with bullies. Heck, I even had a red-headed girl who lived next door (albeit one who was never a viable love interest — it’s only now, more than four decades on, that I’m realising that particular Lana Lang parallel). All of this was far more relatable to me than the office politics of the Daily Planet.

As far as I was concerned, Superboy was a fundamental part of the Superman history. And so was the bottle city of Kandor. And Mr Mxyzptlk. And Beppo the Super-Monkey. And the countless other elements that completely failed to make an appearance in Superman: The Movie.

Yet somehow, despite these reprehensible absences, I loved Superman: The Movie. In a pre-Netflix era, one streamed movies by popping in a video cassette tape that contained a copy of a film that you had recorded during an earlier television broadcast. (A premium ad-free streaming service was attained by carefully pausing the recording during the commercial breaks at the time you made the tape.)

When we got a VCR a few years later, Superman: The Movie was one of the first movies to be swiftly recorded from a television broadcast and filed into the dozen or so films that we had in our collection. We even ensured it couldn’t be inadvertently taped over by using the now-irrelevant VCR life hack of breaking a small tab on the cassette. Safe from accidental erasure, my brothers and I watched the film over and over, gradually learning to tolerate and eventually love the pre-helicopter portion of the movie. (Having said that, for a long time, the tape on the shelf that sat beside Superman: The Movie — the one that contained Superman 2 — was the one more likely to be fed into the VCR. The sequel began with a montage of the good bits of Superman: The Movie then zipped straight into an Eiffel Tower nuke and a trio of Phantom Zone villains. Hard to argue with that as a wee lad.)

But despite how much I loved both Superman: The Movie and Superman 2, the Superman portrayed in those movies wasn’t the Superman I knew. My Superman was the comic book version, with all the detritus built up over an entire Silver Age worth of history.

And the comic book that best summarised that history was 1979’s World of Krypton.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the delivery of DC comic books in Australia was presided over by K.G. Murray Publishing. They had the reprint rights and implemented them by taking multiple issues of (ideally semi-related) DC comics, stripping them of all colour, packaging those issues together in one edition and selling them via newsagencies.

At the time I had no idea about any of this. I didn’t know these were reprints or that this kind of packaging was not how the issues had originally been published. I don’t think I was even aware that they were supposed to be in colour.

All I knew was that I received $1 a week in pocket money, and these Murray comics, at 96 pages for 95c (later, 96 pages for 99c), were designed to fit perfectly within my budget.

In the US, the three-part World of Krypton story was originally supposed to be published as issues 104 to 106 of the Showcase comic book, timed to tie in with the release of Superman: The Movie. Scheduling issues doomed that plan. (Probably for the best, given that the stark crystalline Krypton in Superman: The Movie bore no resemblance to the Silver Age jungle planet seen in the comic book series.) Instead, World of Krypton, the story of the last days of Superman’s home planet, was published in the United States as the first ever comic book limited series.

Here in Australia, the Murray folk weren’t going to look a gift miniseries in the mouth. They packaged up all three issues of World of Krypton (along with a few other miscellaneous stories) and shoved it out there as a complete self-contained back story of Krypton. Was this perfect bait for a young country bumpkin with access to a single shiny one dollar note? You better believe it was.

(A year later, DC comics would release a similar miniseries that outlined the origin of Batman and all his supporting characters. Again, the fine Murray folk threw it all together in one giant 96 page comic. And, again, I handed over my 95c at the local newsagency and happily claimed that one for my collection too.)

I greedily devoured the World of Krypton. The story of Jor-El’s doomed attempts to save his fellow Kryptonians was thrilling. Imagine! A scientist who can see that his planet is doomed but is incapable of convincing those in power to take the necessary steps to save themselves. Wild stuff indeed.

Of course, in retrospect, Jor-El was a terrible scientist. Proper scientists run experiments. Do research. Prove their results. And thereby convince their colleagues of the truth of their discoveries.

It’s one thing to be incapable of getting powerful non-scientist politicians to give up the status quo in favour of saving a planet. We all know how that plays out. But when you can’t convince your fellow scientists — most of whom revered Jor-El as their most gifted intellect prior to all this Krypton-exploding gibberish — you’ve got a problem. Show your working, Jor-El!

Despite this, the story is a rollicking science fiction adventure. Jor-El builds himself an anti-gravity belt that allows him to fly and lift heavy objects. The belt effectively turns him into a Krypton-based superhero, shoehorning into the story the kind of action that fans of his son might enjoy.

In between his belt-driven superheroics, Jor-El also meets and marries Lara Lor-Van (despite the corrupted wishes of the love computer that assesses the viability of all Krypton couplings). He discovers the Phantom Zone. And he builds rocket ships.

Boy, does Jor-El build rocket ships. Sadly, however, his work on interplanetary travel is a complete shambles.

Here’s how Launch Director Jor-El’s space program went down according to World of Krypton:

Unmanned test flight — hindered by the Launch Director’s girlfriend sneaking onto the spacecraft shortly before launch, impacting its trajectory so that it crashes into the moon, requiring the Launch Director to use his anti-gravity belt to fly to the moon to rescue her

Manned orbital mission — rocket lost during flight, only to crash-land back at launch site, with the sedated criminal astronaut on board replaced by his twin brother in orbit (via a second rocket) and apparently given superpowers, going on a crime spree before the Launch Director brought him to justice

Space ark test flight — aborted when a passing alien used a shrinking ray to steal the entire city in which the launch site was based and keep it in a bottle as part of his collection

Manned test flight — rocket lost due to near collision with rogue nuclear missile launched by disgraced former senior engineer of the space program, resulting in the destruction of the (colonised) moon

Test flight with dog — rocket lost due to collision with stray meteor

This is not a successful space program. It’s conducted in seemingly random order, with little to no safety procedures, and a one hundred percent failure rate. It’s no wonder that in the final issue of the story the Krypton Science Council shuts it all down.

Luckily, despite all his rocketry ineptitude, Jor-El still has one spaceship left. The one in which he places baby Kal-El and somehow successfully shoots him off to Earth seconds before his planet explodes and the miniseries ends. Jor-El, a scientist very much of the ‘try, try again’ school.

But infinitely more bizarre than Jor-El’s appalling work as both a theoretical and practical scientist is a stunning comic book cameo. A cameo teased on the front cover of the first issue. Yes, for one panel in the first issue and half of the second issue of the World of Krypton miniseries, Superman — the full, grown-up Superman who is otherwise bookending this tale — is suddenly part of the story, working alongside his dad, trying to save Krypton. He pops up for several pages, gets angry because he forgets that Brainiac was going to steal the city of Kandor and put it in a bottle, then disappears from the story before the climax.

And there’s no real explanation for this for those new to the story. You’re just expected to know that at one point (Superman 141 from 1960 as it turns out), Supes travelled back in time and space to visit Krypton for a while. (He spent a decent chunk of that issue hanging out not just with his Kryptonian parents, but also spying on his Earth parents Jonathan and Martha via a giant space telescope and using a light-year spanning rifle to ensure they eventually hooked up. You’ll believe a man can McFly.)

But the point was this: For two decades, it had been part of DC continuity that Superman had gone back in time to not only completely Back to the Future the bejeezus out of Ma and Pa Kent but also to help Jor-El with his research. And since this was established continuity and the World of Krypton miniseries was designed to be the definitive summary of the planet’s last days, this plot point had to be thrown in there, no matter how baffling it might have seemed for first-time readers.

I don’t recall if it baffled me. I can only assume it did. But on the other hand, I was a child. And children will believe anything.

So if it was an established fact that Superman once travelled back in time to Krypton, then so be it. Just one more piece of worldly information to take in, alongside long division and being scared of girls.

Superhero comic books existed well before I was born. There were decades of stories I had never read. And haven’t read since. And, indeed, will never read. Comic book writer Grant Morrison has made the point that an interconnected continuity of stories such as the DC or Marvel superhero universes are unique pieces of fiction because they’ve grown so enormous over the decades that it’s essentially impossible for any one person to read them in their entirety. (We’ll get back to Morrison later in this series.)

This epically convoluted history is, of course, why something like Superman: The Movie had to strip it all away and start from scratch. It’s why there was no Superboy. No bottle city of Kandor. No Christopher Reeve inexplicably hanging out with Marlon Brando in the first ten minutes of the movie.

World of Krypton, however, chose not to strip anything away. It embraced it all. This convoluted continuity could have been overwhelming. But it wasn’t. At least, not to me. It was intriguing.

I was in. I was all the way in. Origin stories like World of Krypton and The Untold Legend of The Batman gave me my footing in the DC universe. Everything else would build from that.

Next month: To me, my X-Men comics

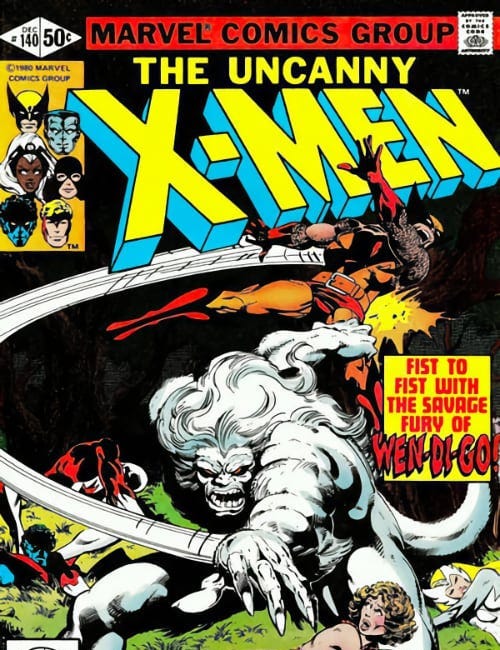

A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — 1980 — The Uncanny X-Men 140

Written by Chris Claremont Pencils by John Byrne Cover date: December 1980 Warning: spoilers for the issue follow One of the fundamental aspects of comic books as a medium — indeed, the fundamental aspect — is the interplay between words and pictures.