A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — 1980 — The Uncanny X-Men 140

In which I discuss the intersection of words and pictures, the grown-upification of superhero comics and Canadian forest monsters.

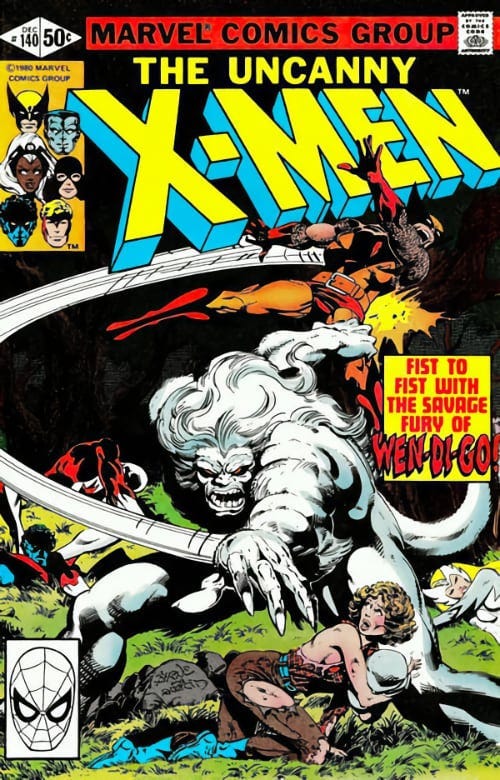

Written by Chris Claremont

Pencils by John Byrne

Cover date: December 1980

Warning: spoilers for the issue follow

One of the fundamental aspects of comic books as a medium — indeed, the fundamental aspect — is the interplay between words and pictures.

If novels and short stories and poems live in the set of written forms of creativity, and paintings and drawings and photographs live in the set of pictorial forms of creativity, then comic books exist in the intersection of those two sets. It’s a hybrid medium with the potential to simultaneously stimulate two very different parts of the brain.

Comic books are not unique in this. Most notably, early reader books also often blend words and pictures. The books’ drawings help new readers by illustrating the simplistic words that they’re only just beginning to learn.

Presumably the fact that comic books share a Venn diagram intersection with books designed for children learning to read helps explain why comic books are so often derided as being only for kids. Well, that and the fact that for many decades, mainstream superhero comic books were created only for kids.

But this isn’t a fundamental truth. There’s no inherent reason why comic books as a medium should target an audience solely of children. (And, of course, in many cultures around the world, they didn’t (and don’t). But I’m talking here about DC and Marvel superhero comics which, in 1980, were the only comic books to which I had easy access. So when I refer to ‘comic books’, please keep in mind my blinkered nine-year-old focus.)

The early 1970s saw restless creators first dabble with the notion that ‘comic books aren’t just for kids any more’. Perhaps most famously, Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams — a writer/artist team with a built-in portmanteau — worked on a Green Lantern/Green Arrow comic book run that tackled a series of Very Adult Themes: Drug addiction. Pollution. Overpopulation. Motorcycle thieves. Robot space juries. Racism.

From a modern perspective it all feels a bit heavy-handed. (“You always have all the answers, Green Arrow!” asserts a smug Green Lantern on the cover of Green Lantern 85. “Well, what’s your answer to that?” he continues, gesturing to Green Arrow’s former sidekick, Speedy, seated at a table adorned with drug paraphernalia. A shocked Green Arrow reacts with appropriate compassion and concern to the revelation that the man he raised as a son is addicted to heroin: “My ward, Speedy, is a JUNKIE!”)

But even if social conscience stories tend to fit uneasily with a man dressed as Robin Hood and his space cop friend who wields a magic wishing ring, there are other ways in which creators can grown-upify comic books. In 1980, a decade after Denny O’Neal Adams’ Green Lantern/Green Arrow, another acclaimed writer/artist pairing was coming to the end of their time working together, a time in which they’d brought a different kind of sophistication to their comic books.

That writer/artist pair was Chris Claremont and John Byrne. Over the course of their 35 issues together on X-Men (aka Uncanny X-Men), they grew the series from an unloved bi-monthly book that half-assedly reprinted old stories to Marvel’s best-selling and most critically acclaimed title.

The secret to their success was a completely different way of telling more mature stories.

Yes, X-Men contained its share of Very Adult Themes. Indeed, the mutant characters in the book and the fear and hatred they face are easily read as analogues to real-world minorities and the prejudices they’re forced to endure.

But unlike Green Lantern/Green Arrow, such messaging was primarily subtext. An obvious subtext, to be sure, but subtext nonetheless. On the surface level, the X-Men were superheroes doing superhero stuff in their ongoing superhero adventures.

And it’s that ‘ongoing’ bit that was where Claremont and Byrne showcased their particular version of grown-up comics.

Comic books are generally distributed monthly. But for many decades each issue of a superhero comic book contained stand-alone stories. That way, anybody could pick up a book, read it and enjoy a complete tale with a middle, end and beginning (albeit rarely in that order).

Of course, as we saw in World of Krypton, these stand-alone stories might still impact later ones. A fundamental premise of both the DC and Marvel superhero universes was that their characters experienced all the adventures told in their books (although we’ll get to some exceptions to this rule later). To maintain this premise required some form of continuity. That is, once a particular issue established an aspect of a character or their history, that aspect held from then on. (Or, at least, until it was undone in a later issue.)

Continuity was fine with me. I liked continuity. Continuity meant things made sense. (Even if it meant that a 1979 comic book was beholden to one from 1960 and the incredibly baffling story element it introduced.)

But Claremont and Byrne dealt in more than continuity. They dealt in serialisation. Yes, each issue of X-Men stood more or less alone-ish. But they also combined to tell a larger, ongoing story.

To apportion credit fairly, Claremont started that larger, ongoing story before Byrne arrived. And he continued it long (long) after Byrne left. Claremont would eventually write the book for a decade and a half, teaming up with a variety of different artists to tell a massive ongoing serial that was part superhero adventure, part soap opera, part science fiction romp, part weird holiday in the Australian Outback. But it was the three year collaboration with Byrne that was the undoubted peak of Claremont’s time on the X-Men.

Together the duo created not one, but two of the all-time great X-Men stories. Indeed, the two that generally top most lists of all-time great X-Men stories.

The first was the epic Dark Phoenix saga. Founding character Jean Grey — a mutant with strange telepathic and telekinetic abilities — is slowly corrupted over multiple issues by the insidious power of the Phoenix, a cosmic force of destruction and rebirth (think David Bowie). She and her fellow X-Men fight (with varying degrees of success) a number of nefarious forces who wish to either a) control her power, b) punish her for the genocidal use of that power or c) eventually adapt the story about that power into two (2) unsuccessful movies.

The Dark Phoenix Saga is epic comic book story-telling, using the serialised nature of the medium to show the slow, gradual demise of one of the most beloved characters in the book. Jean Grey is not just the character who kickstarted the very first X-Men issue in 1963. She’s so fundamental to the comic book universe in which she resides that her original sobriquet was ‘Marvel Girl’.

The corruption of Jean may not have had the Emmy award-winning grown-up sophistication of Breaking Bad, but it shared its spirit. (And, to be fair, did Walter White ever face the Shi’ar Imperial Guard in a battle on the surface of the moon to avoid punishment for his crimes? Answer: no, he did not. Advantage: X-Men.)

Claremont and Byrne’s other classic storyline was Days of Future Past, a time travel story starring new X-Men member Kitty Pryde (a mutant with the strange ability to provide a new relatable viewpoint character). A version of Kitty from the far-flung dystopian future of 2013 returns to the past to try and undo the events that led to her doomed timeline. It’s a horrifying world in which giant robots called Sentinels hunt mutants, the X-Men have been reduced to a cowering rabble of desperate survivors and twerking is the predominant dance move.

Days of Future Past not only allowed readers the dark, grown-up thrill of seeing a timeline in which their heroes were defeated and murdered. It also foreshadowed future threats to the X-Men and gave sufficiently dedicated readers the opportunity to embed themselves even more deeply into Claremont’s ongoing serialised story. True X-Men fans could now look for clues in the ongoing monthly story, searching for hints that this dystopian future (or a variant thereof) might come to pass.

The Days of Future Past storyline also got a movie adaptation — one in which the ultimate goal of the film seemed to be, sensibly, the undoing of the first of the terrible Dark Phoenix movie adaptations.

However, the Days of Future Past story more or less concluded Byrne’s run on the book. He had one further issue (issue 143) in which Kitty, alone in the X-Mansion, was attacked by a seemingly unstoppable alien and had to destroy virtually the entire building in order to prevent it from killing her. This story also had a successful movie adaptation (Alien), albeit one that came out in cinemas a year before the comic book was written. No idea how they did that.

I had a copy of X-Men 143, Byrne’s last issue in my collection. Of course, I didn’t know that it was Byrne’s last issue at the time. I didn’t even know who Byrne was. Or Claremont. The idea that comic books had individual creators of whom I could keep track was completely alien to me. As alien as the alien from the Alien movie on which the alien in issue 143 was based.

Apart from X-Men 143, I also had X-Men 130, a minor chapter of the Dark Phoenix Saga. Later, I’d pick up X-Men 148. And X-Men 157.

So I was clearly intrigued by the X-Men and willing to purchase them under certain conditions. The X-Men books even had some clear advantages over the DC comics that I usually preferred. For one thing, the X-Men comics were in colour, exactly the same as the US versions. (As you may recall from last time, the DC comics in Australia were published in black and white 96 page anthologies.)

But there was a simple indivisibility here. X-Men had a 50c cover price. In 1980, $1 Australian dollar equalled roughly $1.50 US dollars. Which fits with my vague memory of X-Men comics being roughly 30c at the time. Certainly that would have been the ball park price.

But buying an X-Men comic for 30c meant that I only had 70c of my pocket money left. Not enough to get any more comics — maybe another Marvel comic, but they were sparsely populated on the local newsagent shelves.

The idea of saving the 5c from each of the 96 pages for 95c DC offerings and picking up a bonus X-Men comic every six weeks or so didn’t occur to me. Or if it did, it wasn’t a plan that stuck. The arrival of X-Men comics was too unreliable in those days to make plans that required a six week timeframe to see to fruition.

All of which meant that I was completely oblivious to the sophisticated grown-up serialised storytelling that Claremont and Byrne were doing. I missed almost the entire Dark Phoenix saga. Days of Future Past also slipped me by, albeit only just. I literally had the issues either side of it — X-Men 143, the Alien issue and X-Men 140, the issue I’ve officially designated as my 1980 comic book.

Looking back on it, there’s nothing particularly remarkable about X-Men 140. It’s an issue focused mostly on Wolverine (a mutant with the strange ability to be both down-to-earth yet have adamantium claws that make the sound ‘SNIKT!’) and Nightcrawler (a mutant with the strange ability to look like a very cold elf) fighting a Canadian forest monster named Wendigo, eh?

There are other subplots in the issue — Colossus removes a tree stump from a paddock, Storm rejects a pickup artist. Kitty has a dance instructor. But mostly it’s just one enormous, beautifully drawn fight.

And that’s how X-Men hooked me. If comic books exist as an interplay between words and pictures, then there are two avenues by which they can entice new fans.

The serialised grown-up story-telling that brought the book so much acclaim elsewhere didn’t grab me at the time. Even if I’d bought the books consistently enough to notice its ongoing grown-up story, I may not have appreciated it. I was, after all, very much not a grown-up in 1980.

I was, however, drawn in by the drawings. I didn’t know much about art, but I knew what I liked. And what I liked, seemingly, was stunningly rendered pictures of monsters and the mutants who fought them.

And that’s the much more down-to-earth way the X-Men got their claws into me.

SNIKT!

Next month: Saving the Waynes