A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — 1981 — Detective Comics 500

In which I discuss superhero ageing, parallel Earths and my favourite ever Batman story

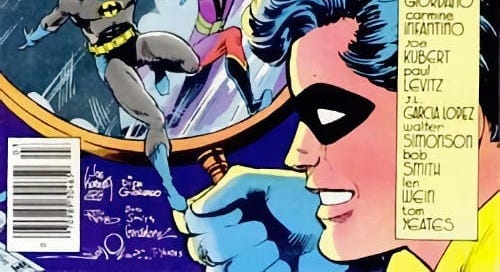

Written by Alan Brennert

Pencils by Dick Giordano

Cover date: March 1981

Warning: spoilers for the issue follow

Time works differently when it comes to superhero comic books.

As we’ve already seen, one of the core conceits of a shared comic book universe such as the DC universe or the Marvel universe is that all of the adventures that take place in the comics are part of a character’s history. This remains true no matter how preposterous or challenging that might be to internal consistency, and even if it inexorably leads to a time-travelling Superman appearing smack bang in the middle of the origin story of his father.

But it’s not just the struggle to remain internally consistent that bedevils lovers of superhero comic book continuity. It’s the sheer number of adventures in which some of these heroes find themselves embroiled. For those in a monthly comic book, it’s twelve conflicts — most of them life-threatening — to negotiate each and every year. That number doubles if the hero in question has two monthly books (as Superman and Batman did in 1981, with Action Comics and Detective Comics respectively to go alongside their namesake comics). It increases still further if they have a team-up book in which they help other, less obviously marketable, heroes in their adventures (as both Superman and Batman did again with DC Comics Presents and The Brave and the Bold respectively). Oh, and don’t forget to count the monthly book where Superman and Batman teamed up with one another (World’s Finest). And, of course, their regular appearances as part of DC’s premier superhero team in Justice League of America. That’s roughly 60 adventures per year for each of Superman and Batman, not including any guest appearances they might have in any other books. Superman at least has the advantage of super-speed to help him zip from adventure to adventure. But Batman? Batman’s just this guy, you know?

For the most part, the writers of the comic books hand-wave this unrealistically packed schedule of adventures away. Certain stories (and, once serialised story-telling became the norm, certain storylines) are ignored. Only major events are considered part of the continuity canon, with the rest of the monthly escapades compressed instead into ‘other miscellaneous adventures’. Nobody looks too closely at it. A kind of consistency is maintained, despite the colossal number of events that are forced into a timeline.

But there are obvious limits to this. Superman, after all, was created in 1938. Batman in 1939. Both characters have been around since World War 2 and yet are still written to this day as if they’re aged in their late 20s or early 30s.

Heck, even in 1981 when I was reading this story for the first time, it was impossible for them to have had adventures set in the 1940s and still be viable modern-day superheroes.

Luckily the comic creators — particularly at DC — had a way around this too. At the time, they posited a multiverse of universes and Earths. The two main Earths were known as Earth-1 and Earth-2. Earth-1 was the modern day Earth on which all the 1960s and 1970s (and now, early 1980s) comic book stories had taken place.

But then there was Earth-2, which shifted everything back a couple of decades. That Earth was where the World War 2 adventures had taken place, along with those of the 1950s comic books. These earlier adventures were deemed to have taken place to different versions of Batman and Superman. The Earth-2 versions of the characters.

The delineation point between the Earth-2 and Earth-1 adventures was a little hazy for Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman. Those three characters had remained in continuous monthly publication since their debuts. At no point did anybody explicitly say ‘okay, from this month we’re dealing with a different version of the hero’. Instead, they just gradually Ship of Theseus-ed their way from Earth-2 to Earth-1 characters.

For DC characters other than Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman, however, the delineation was much clearer. These other characters had possessed the good sense to be cancelled for poor sales at the end of the Golden Age of comics. So when the new Flashes and Green Lanterns and Hawkmen and Hawkwomen returned in the early 1960s, they returned with completely different identities and origins. Which made things very simple. The old, cancelled heroes were the Earth-2 versions of the characters. The new ones were the Earth-1 versions.

Except, of course, by 1981, they weren’t actually all that new at all. As neat as the Earth-1 and Earth-2 explanation was, there was an obvious ticking clock on this conceit. (A ticking clock that had about four years left on it as it turned out, but we’ll get to that when I cover 1985.) The adventures attributed to the Earth-1 versions of all these characters came from roughly two decades’ worth of comics by now.

And even when you did the hand-waving tricks mentioned above and smooshed a whole heap of the less memorable monthly issues of the comic book into ‘miscellaneous adventures’, there was still a lot of history to reconcile. Too much history, to be frank. The writing was on the wall. Sooner or later there would have to be new versions of not just Superman and Batman, but all the characters, all taking place on a whole new Earth.

(You may think that this next generation of characters would exist on Earth-3. But there are a few reasons why you’d be wrong for thinking that. For one thing, the counting system was already messed up. The older version was Earth-2. The newer one, Earth-1. If anything, the new newer version would have to be Earth-0. Especially since Earth-3 was already taken and was established in DC continuity as a morality-inverted universe where all the superheroes were evil and all the supervillains were good.)

(Marvel, for what it’s worth, did things somewhat differently. The only main character they had that tied to something as massive as World War 2 was Captain America and, fortunately, his existence in the modern Marvel universe came about after being frozen in ice. So Marvel simply extended the number of years he was frozen. At first, it was just a couple of decades, with him being unfrozen in the 1960s. But as real time moved on, Cap’s unfreezing came later and later and all the various Marvel adventures just moved forward in time. The necessity for Tony Stark’s Iron Man suit, for example, originally came from injuries suffered in the Vietnam War. But as real time moved on, Tony was later first injured in the 1990s Gulf War and, later still, Afghanistan. Fortunately for Marvel comic book continuity, there are always fresh wars in which Tony Stark can be initially wounded.)

But back at DC, the Earth-1/Earth-2 conceit was on its last legs and, in 1981, it was unclear what would come next.

All of which brings us to my comic book for 1981, Alan Brennert’s magnificent ‘To Kill A Legend’. Technically, I’ve listed this as Detective Comics 500, the comic book in which the story ‘To Kill A Legend’ was first printed. But at the time, I didn’t own Detective Comics 500, which was an anniversary issue that contained several stories celebrating the many heroes that had appeared in Detective Comics over the decades.

Instead, I first discovered this story (and, to be clear, ‘To Kill A Legend’ is what this piece is about — I couldn’t care less about any of the other stories in Detective Comics 500) in what was called a ‘Blue Ribbon Digest’ — a tiny reprinting of, in this case, the best stories of 1981. This was, for many years, a prized possession. It contained samplers from a number of different DC heroes, and the best stories involving them for that year.

There was a tale about Superman trying to save Lois Lane and Lana Lang from the disease that killed Ma and Pa Kent. Another one featured a hot new superhero team called ‘The New Teen Titans’, who did more or less nothing in their story, but, thanks to artist George Perez, did it beautifully. Elsewhere, Green Lantern raised the dead, Captain Marvel super-villain Dr Sivana was given a Nobel Prize and grizzled bounty hunter Jonah Hex got drunk and shot a scarecrow.

But easily the standout story in the Best of 1981 digest was ‘To Kill A Legend’, which played with this looming instability of the Earth-1/Earth-2 conceit.

The story’s premise was that every twenty years, there’s a parallel Earth on which a new set of Wayne parents is about to be murdered, inspiring young Bruce to eventually swear vengeance and take up the mantle of the bat.

‘To Kill A Legend’ posited that we’d spent enough time on Earth-1 now for the anniversary of that night to be coming around. So the Phantom Stranger — a mysterious mystical being in the DC universe whose motives and powers remain deliberately unexplored (think: Bill Murray) — meets up with Batman one night and offers him the opportunity to go prevent the one crime he’d never been able to stop: the murder of his parents.

Already we’re in similar territory to Superman’s visit back to Krypton just prior to its explosion. But as story premises go, this is much, much better. Superman was never going to be able to stop the explosion of Krypton. At least, not without some fundamental time travel paradoxes riddling our comic books. But Batman wasn’t travelling back in time. He was travelling to a parallel Earth. Which meant there was nothing whatsoever preventing him from saving his parents.

Well, almost nothing whatsoever. For while Batman is immediately delighted to find himself on a parallel (and sensibly unnumbered) world where his parents are alive and a younger version of himself lives a happy life with them in a stately manor, Robin is noticeably less delighted. (The Phantom Stranger has allowed Robin to tag along on this adventure for reasons that remain typically mysterious at this early point in the story.)

Robin instead perceives the Bruce Wayne of this Earth as being a spoilt brat. Worse, he does some research (in an actual library, bless his heart) and discovers that there’s no Krypton in this universe. And, bizarrely, no heroic mythology at all. No Robin Hood. No King Arthur. No Sir Donald Bradman. Without such mythology, wonders Robin, where will superheroes come from in an hour of crisis?

Robin puts forth the theory that unless the Waynes are murdered, inspiring young Bruce to become Batman, this might be a world without superheroes. ‘Who would want to live in such a nightmarish hellscape?’ he asks Batman. ‘Do we dare condemn any world to a Batmanless fate?’

Batman fobs off Robin’s theory. He’s instead working on tracking down the murderers of his parents, in accordance with the premise of the story. He’s got a substantial head start in this quest. After all, he solved that particular mystery on his own Earth hundreds of issues earlier, tracing it to a hit arranged by Gotham City mobster Lew Moxon. But despite easily scaring the shit out of this Earth’s Moxon, who’d never seen — or even contemplated the idea of — a grown man dressed as a bat, Batman isn’t making much progress. Particularly since he also has a young cop named Jim Gordon on his case.

Gordon’s pursuit culminates in a magnificent scene where the young lieutenant corners Batman and pulls a gun on him. Will Batman fight his way out of this mess? Use one of the myriad of improbable gadgets in his utility belt to make his escape? Bribe him with some of Bruce Wayne’s millions? Nope. Instead, he simply talks Gordon into letting him go free, by convincing him of their friendship on his Earth.

This allows Batman to finally track down this Earth’s version of Joe Chill, the man who killed his parents. But rather than being hired by Moxon for the Wayne hit, Chill has instead been fatally shot by the mob boss. Why? Because when Batman confronted Moxon earlier in the story, he let slip Chill’s name as the Waynes’ killer. And Moxon’s no dummy. Chill is off the table, assassin-wise. Somebody else has been hired to kill the Waynes.

Meanwhile, with Batman busily talking down Gordon and investigating the dying Joe Chill, the Waynes are suddenly off to the movies. Robin knows enough of Batman’s origin story to know that the movie-watching precedes his parents’ murder, so even though this trip to the cinema is five days earlier than scheduled, he follows them.

(Brennert waves his hands and talks some gibberish about the five leap years over the course of twenty years and how the extra days in the calendar don’t count for cross-multiversal synchronous events. Sure, fine, whatever. Even as a ten year old, I knew this was just a contrivance to make the story work. But I didn’t care, because the story did work. It worked like crazy.)

As Robin follows the Waynes, he’s still unsure about whether he should be saving them and condemning this world to Batmanlessness or letting them die to give this world a much-needed hero.

It’s only when Robin sees the new mugger pull the gun on the Waynes that he realises that, regardless of any greater philosophical qualms he might have, he can’t just stand by and watch two people be murdered in cold blood.

He goes to spring to their rescue.

But Batman is already there. He swoops down from nowhere and prevents the killings from taking place, beating up the mugger (who, fittingly, exhibits no Chill whatsoever) and leaving him for the police. With the Waynes saved, the Phantom Stranger returns to take Batman and Robin back to their own Earth.

“Will we ever know what happened to him?” asks Robin, still concerned about the bigger picture.

“Nope,” says the Phantom Stranger, who can often be a dick about such things.

And we are left to ponder what might happen in this world.

Except we’re not, because we have a one page epilogue to wrap up the story. After the events of that night, we see the very much alive Waynes talking to one another about young Bruce. About how since the attack, he’s been much less of a little shit. How he’s now interested in criminology. And detective work. How he’s training, doing chin ups on tree branches. Dr Thomas Wayne quips that maybe they ‘should get mugged more often’. (Not cool, Doc.)

We also learn that young Bruce will forever remember the mysterious bat-like figure that swooped in and saved his parents that night.

The final panel image shows a young Bruce walking down the driveway after his new exercise routine, with the Batman shadow with the pointed ears and cape stretching out before him. The final captions tell us that, many years later, he will choose a direction for his life, and that decision will not be based on grief, or guilt, or vengeance…

And then the final caption: “But of awe and mystery and gratitude.”

Not only has Brennert given us a story in which Batman saves his parents, he underpinned that story with a moral quandary that had us hoping — at least to some degree — that he’d fail to do so. And then surprised us with an ending that gave us both the triumph of Batman undoing the tragedy that made him, while simultaneously inspiring a very different origin for this world’s version of the caped crusader.

It’s a great twist ending. One that I adored when I was ten, and one that I love to this day. I’m not alone in this. Along with being the standout story in DC’s best comics of 1981, this story also appears in ‘The Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told’, ‘Batman in the Eighties’, and ‘Detective Comics: 80 Years of Batman’.

As it turned out, the young Bruce in this story wouldn’t become the new Batman that replaced the Earth-1 version. But if he had done so, I would have been perfectly satisfied with that transition.

For I found (and find) this story strangely moving. I can’t completely pinpoint why, but I think it’s because of its optimism. Batman is one of the most famous fictional characters in the world. The inciting incident that made him Batman is almost as famous, and fundamentally woven into the fabric of this story, permeating every panel. Yet, as omnipresent and foundational as the darkness of Batman’s origin story seems, Brennert, at the last moment, puts forth an alternative, more optimistic origin. You can have a Batman without the tragedy that inspired him. You can have a Batman inspired by forces of light. I like that. I like that a lot.

The origin of this Earth’s Batman captivated me and even though he was never revisited by DC creators, I revisited him many times. I read this story over and over and over as a child, delighting in the tale long after the initial surprise of the twist ending had been lost.

In fact, I read this story so many times that even in writing this, forty years later, I didn’t have to look up that closing panel and image of the story when I quoted them above. I remembered the image, and especially the words, as vividly as if I’d read them yesterday.

Like I say, time works differently when it comes to superhero comic books.

Next month: Teamwork makes the dream work