A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — 1985 — Crisis on Infinite Earths 7

In which I discuss Cantorian loopholes of uncountability, purple-haired prototype Goggleboxers and things never being the same again.

Written by Marv Wolfman

Pencils by George Perez

Cover date: October 1985

Warning: spoilers for the issue follow

One of the many interpretations of quantum mechanics is called the Many Worlds Hypothesis. It suggests that instead of the one universe that we experience in our day-to-day life, that there are multiple realities that all exist alongside one another. Under the Many Worlds Hypothesis, various seemingly counter-intuitive results such as the double slit experiment, Schrodinger’s Cat or the how-many-quarks-can-you-squeeze-into-a-trolley problem can best be explained by this multiverse of many worlds.

Of course, these days, multiverses are all the rage. Dr Strange is nuts for them, bringing them into the Marvel Cinematic Universe like nobody’s business. Rick and Morty traverse them willy and/or nilly. (And because it’s a multiverse, there is a universe in which it’s Strange and Morty having all the zany, presumably strangely mortifying, multiverse adventures. (“Aw, gee, Doc. Is… is… Thanos really going to win and everything?” “’fraid so, Morty.” (holds up one finger, belches).)

But even just a few short decades ago, the idea of a multiverse was not common, and certainly not the preferred quantum physics interpretation of how the subatomic world works. (It may still not be — I’m not entirely sure to what extent the mainstream dogma of quantum mechanics is impacted by the decrees of Kevin Feige.) The preferred interpretation — the Copenhagen Interpretation, named for Neils Bohr’s favourite 1920s Danish nightclub — suggests that all possible outcomes of quantum experiments exist simultaneously in a distribution of alternatives until they are observed, at which point they collapse into one choice only.

Personally, I never liked the Copenhagen interpretation. It always seemed needlessly complicated. What was so special about observers of experiments? And what qualified as an observer, anyway? A rat? A microbe? An incel? How sentient did the observer have to be? If a box containing a Schrodinger zombie cat was opened in the forest and only a tree was there to see it, did that collapse the wave form?

No. All the observer stuff seemed far too convoluted and subjective to my untrained mind. An objective multiverse of options, the details of which we only observed once we checked, always made much more sense to me. (So much so that I was inordinately pleased when physicist David Deutsch wrote one of my very favourite books on science The Fabric of Reality in which, to my mind, he provided a compelling proof of the existence of the multiverse in his opening chapter.)

But it has occurred to me that one of the reasons I’ve always been so predisposed to the multiverse explanation of our reality was because of my early love of comic books. From the earliest superhero stories I can remember, the multiverse was part of it. Earths-1 and 2. Earths-C and X. Earths shamefully without designations. Earths on which different variations of the superheroes lived. It was so commonplace, and explained so logically to me on at least an annual basis, in the various Justice League of America/Justice Society of America crossovers, that I couldn’t understand how anybody wouldn’t countenance it. (To Deutsch’s eternal credit and/or odium, his proof of the existence of the multiverse at no point relied upon crossovers of crime-fighting superhero teams.)

The various JLA/JSA crossovers were some of my favourite crossovers of them all. Earth-1 and Earth-2 heroes working together to resolve various ‘Crises’ on an annual basis. Crisis on Earth-X (the crisis of defeating World War 2-winning Nazis). Crisis on Earth-Prime (the crisis of a rogue timeline in our world in which the Cuban missile crisis went kablooey — you remember that). Crisis on Earth-S (the crisis of shoehorning the Shazam family into the DC Universe). And so forth. Yes, please. And yes, some more.

And then, in 1985, DC’s fiftieth anniversary, a comic book appeared in my local newsagency. It was titled ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’. Worlds will live, it promised. Worlds will die. And nothing will ever be the same again.

Yikes!

Secret Wars hadn’t arrived in my little country town. But the Crisis on Infinite Earths had. And not in reprint black and white Murray Comics form. This was, essentially, the original comic (albeit one that had seemingly been reprinted on lower quality paper — again, no doubt a short-lived Australian licensing deal of the time that I have no interest in exploring further).

The first issue hooked me. The mysterious Monitor and his assistant Harbinger gathered together a variety of eclectic heroes (and a villain or two) from various times across primarily Earths 1 and 2. And told them all a story about a threat to the entire multiverse.

We saw Earth-3 die. Earth-3 was the Earth on which everything was backwards. Heroes were villains. Villains were heroes. Dogs were aloof. Cats were friendly. And Bizarros were presumably normal everyday citizens.

In particular, Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, et al were villains on Earth-3. And Lex Luthor was a hero. Except, in the end, the villainous Justice League — The Crime Syndicate, as they were brazenly known — died as heroes, trying to fight an ominous white wall of nothingness that was, quite literally, erasing them and their universe from existence.

The Monitor’s makeshift team were sent to defend giant golden tuning fork towers scattered through time, space, universes and the first four issues of the series. The tuning fork towers were designed to reverse cosmic polarity via unobtainium-fuelled diodes or some such and would come together as part of the Monitor’s plan to save the multiverse.

The heroes defended the towers bravely. They fought off the big bad’s army of shadow monsters. Harbinger was corrupted. The child of Earth-3’s Luthor and Lois Lane was rocketed to the care of the Monitor just as their universe died. A purple-haired prototype Goggleboxer named Pariah was cursed to witness the demise of every universe before being snatched away to witness the next one. And so on and so forth.

And as this all went on, the white blankness that threatened to erase from existence the literal comic book pages we were reading came closer and closer. At the end of the fourth issue, the Monitor was murdered by the corrupted Harbinger.

And with his demise, the whiteness erased the last five of the multiverses (Earths 1, 2, S, 4 and X).

A thrilling cliffhanger, albeit one that, to this day, I find numerically infuriating. If the enemy — and, dear reader, you will be delighted to hear if you didn’t know already, that his name is the imaginative ‘Anti-Monitor’ — was wiping out a universe at a time, then how did he get from an infinite number of universes down to the last five? I mean, uh, are we supposed to believe he found some, like, Cantorian loophole of uncountability or some such? Seemed pretty unlikely to me as a fourteen-year-old star mathematics student. Seems just as unlikely to me now as a much less stellar middle-aged man who only vaguely recalls the details of his degree in mathematics.

After issue four and the demise of the last surviving infinity-defying universes, there came a moment of perhaps profound symbolism. The Crisis on Infinite Earths comic book also disappeared from my local newsagency shelf. There was no issue five, or six, or seven…

The DC universe had been wiped out. Not just in comic book terms. But also in literal local newsagency purchasability terms.

And that was where the story ended, as far as I was concerned.

My access to comic book worlds had lived. My access to comic book worlds had died. And nothing would ever be the same.

For about six months or so.

As a fully-fledged stereotypical fourteen-year-old 1980s nerd, I was also, of course, into role-playing games. I dabbled in Dungeons & Dragons, toyed with Traveller, ran with Runequest and many, many others, regularly DM’ing (and TM’ing and RQM’ing) adventures for my brothers and other neighbourhood kids.

Which meant that I also picked up the occasional RPG magazine such as White Dwarf (this was not racist!). And it was in one of these magazines that I first saw an ad for a store in Melbourne called Minotaur Books. That advertisement suggested that they sold all manner of RPG paraphernalia — rule books, dice, adventures, anti-bully pepper spray and the like. And then, right at the very bottom of the ad, an almost apologetic ‘And we sell comics too!’

As it turned out, this was merely a piece of savvy advertising honed specifically for the RPG magazine in which it was placed. Because comic books wasn’t an afterthought for Minotaur Books.

It was an actual comic book store. If you could imagine such a thing.

Even better, it was a comic book store that allowed for a mail order pull list. I sent off for a catalogue, budgeted extremely carefully to get to their minimum standing order of five regular monthly books and soon started receiving comic books in the mail. As if by magic. (Or by Australia Post, which was a form of magic, surely.)

I didn’t receive any Crisis on Infinite Earths issues in this fashion — the series was done by this stage — but I did receive some of the later issues of Who’s Who: The Definitive Directory of the DC Universe. In particular, I received the issue that covered Superman (alongside the equally renowned Stripesy, Stone Boy and Steppenwolf).

And was horrified to discover it was all wrong.

Every word of it.

How strangely mortifying for the editors.

Yes, they had the Earth-2 Superman more or less right. But the Earth-1 Superman was totally messed up. None of the knowledge that I’d built up over the years was reflected in the Superman entry.

I had only a very vague idea of what was going on. There was some kind of letter column explanation that clarified that the Superman in the Who’s Who was reflecting the new rebooted origin established by John Byrne as a result of a mini-series that spun out of the end of Crisis on Infinite Earths.

On a Red Riding Hoodesque vacation to visit my grandmother shortly after, I uncovered further clues, in the form of some issues of this Byrne reboot — Man of Steel.

And began to glean that the multiverse — my beloved multiverse — was no more. At least, not as far as DC was concerned. Somewhere in between issue four of Crisis on Infinite Earths and issue twelve, the final issue, the multiverse had been replaced by a single unified DC universe.

There were now two histories of DC. The one I’d known. The one I’d grown up with. The pre-Crisis DC universe, with its various parallel Earths. With a World of Krypton in which Superman travelled back in time to help his dad with some research. With a Batman who traipsed off to another universe to save his parents, accidentally triggering an alternatively-origined Batman. With a cartoon rabbit who ate a radioactive carrot, started a superhero team that lived in a headquarters in the shape of a Z that necessitated the use of diagonal elevators, before being cruelly cancelled from underneath me.

My DC universe.

And now there was this, the post-Crisis DC universe. One where all my knowledge was now worthless. A universe that, quite literally, had no place for Captain Carrot or his Zoo Crew.

Slowly but surely over the next few years — and I don’t even remember how — I started finding issues of Crisis on Infinite Earths as I tried to piece together how this transition took place.

Eventually I found issue seven, the one I’m designating as my 1985 comic.

This was the big one. A double sized issue. The secret origin of the Monitor. The anti-secret origin of the Anti-Monitor. The parable of Pariah. The history of the DC multiverse.

But most importantly, the one where Supergirl died.

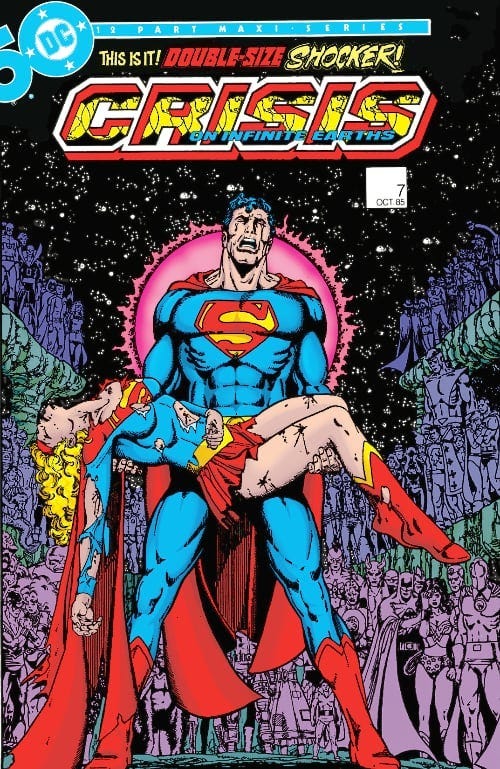

They didn’t even try to hide her death. The cover had her dead in Superman’s arms as he sobbed uncontrollably, while all of the other heroes looked on, devastated (notable exception: Dr Fate, whose helmet hid a heartless yawn).

It was a great issue. The powerful cosmic-level heroes (Superman, Captain Marvel, Firestorm, Captain Atom, Wonder Woman, David Hasselhoff, Wildfire et al) taking the fight to the anti-Monitor on his own turf. In an anti-matter universe where their non-anti-matter powers could not be relied upon.

They fought him to a standstill, putting a halt to whatever nefarious plan he had at that stage (collapsing the universes in on one another, I believe, like an unconvincing quantum physics explanation). And it was Supergirl who did all the damage. After the Anti-Monitor accounted for Superman, she raced fearlessly to his rescue, taking on her far more powerful opponent and almost besting him with her protective fury, only to eventually lose her life while urging others to get to safety.

She defeated the Anti-Monitor long enough to save the (still illogically finite) remaining universes and send him scurrying off to the dawn of time where he’d inexplicably wait for the final conflict in issue twelve.

And then, Supergirl (aka Kara Zor-El, aka Linda Lee aka Helen Slater) died, in her cousin’s arms.

It was wonderful, melodramatic stuff. Drawn exquisitely, because did I mention that all the Crisis on Infinite Earths art was done by the great George Perez?

One of the great comic books of all time. With a cover that’s been homaged endlessly ever since.

Supergirl was gone.

And so was the pre-Crisis universe.

I’d track down the other issues over the next year or so. Eventually, I got issue ten (in which the multiverse was officially wiped out and a single universe took its place) and pieced it all together.

Worlds had lived. Worlds had died. And nothing was ever going to be the same.

I still got my post-Crisis comics shipped to me from Minotaur. My Justice League of America comics would come. My X-Men (sensibly side-stepping all the Crisis stuff by the technically permissible tactic of being a Marvel comic) comics would come. But neither were as good as they’d been just a few years earlier. (There was some kind of sewer-based massacre happening in the X-Men and that didn’t seem like the kind of fun I’d signed up for. I cancelled my subscription to that shortly thereafter. I half-heartedly stuck with the JLA, even though the team was now a whole heap of lame heroes — Vibe! Gypsy! Steel! Vixen! Dale Gunn! — being beaten up by pretty much whoever they came into contact with. Heck, in one storyline they were caught in a forest fire, which was not exactly the kind of high concept superhero storytelling that tended to thrill me.)

The last issues of the Who’s Who would also come. But they now told a history of a DC Universe that was different to what I remembered. And I was struggling to muster much enthusiasm for any of it.

My excitement at getting a Secret Wars style crossover for the DC heroes had come at a terrible price.

Hypothetically, there were many worlds in which a version of me might have my love of superhero comic books reignited. But it was no longer certain that this world would be one of them.

Next: A return?