A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — 1986 — The Dark Knight Returns 1

In which I discuss taking Batman seriously, non-illuminating sample panels and Nikola Tesla's colouring wrench

Written by Frank Miller

Pencils by Frank Miller

Cover date: June 1986

Warning: spoilers for the issue follow

There are some years where a medium reaches a creative peak.

In movies, for example, 1999 is revered as a great year. A swathe of innovative or weird or gigolo-centric movies swept through cinemas worldwide. The Matrix, The Sixth Sense, Fight Club, Being John Malkovich, Galaxy Quest, The Blair Witch Project, American Beauty, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace and Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo, to name just some.

In music, you have years such as 1967, which saw not just the release of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but also Aretha Franklin demanding respect, Jimi Hendrix questioning levels of experience, The Doors urging fires to be lit and other seminal album and single releases from The Velvet Underground, The Rolling Stones, Procol Harum, and assorted Monkees, Turtles and Troggs.

For comic books, 1986 is renowned as one of the great years. A year that turned the medium upside down (not literally — comics were still, for the most part, read from top to bottom) and challenged all preconceptions. A year in which some of the greatest comic books ever created were published. A year in which those outstanding comic books made spectacular, Hulk-like bounds towards the much-vaunted goal of the medium finally being taken seriously.

And I didn’t read any of them.

In 1986, I read only a handful of comics. I still had my mail order comics coming — a bit of Justice League, a bit of DC’s Legends crossover mini-series (which posited the terrifying metatextual question ‘what if people didn’t like superheroes?’). Some Batman. But nothing much else. I didn’t have the budget for much else.

I no longer bought comics from the local newsagency. However, in early 1987, I did buy an issue of the Amazing Heroes comic book magazine. I do not know why. It can’t have been the cover image, because that featured an unremarkable superhero team I’d never heard of — The Justice Machine. (‘A machine that delivers justice? Sounds fascinating, Nikola. But why build it out of third-rate cookie-cutter superheroes?’ ‘Shut your mouth and hand me that colouring wrench.’)

There were some interviews in the magazine. A reprint with Gardner Fox, for example, the JLA writer of the early 1960s who’d apparently just died. A few other bits and pieces, including the schematics of this so-called ‘Justice Machine’ superteam. Nothing that, on its surface, would seem to justify me buying the magazine. I can only assume I inexplicably had money to burn and was craving some behind-the-scenes secrets of the industry.

But right near the back of the magazine was something interesting. A list of the 25 best comic books of 1986. The pre-internet version of an online listicle: The 25 AWESOME 1986 Comics That Bullies Who Don’t Take The Medium Seriously Don’t Want You To Know About!

It was the first inkling I had that I was missing out on something special in the superhero comic book universe. But not enough of an inkling to justify me rectifying the situation. (Although again, at that point, I had no money with which to rectify the situation, regardless of inkle-level.)

The countdown began with an unranked list of fifteen very good comics — one of which I’d read (more on that one comic shortly).

The Very Good Fifteen was then followed by the official Top Ten, at least according to the writer. (That writer was a very unpleasant man named Gerard Jones, who I recommend you Do Not Google. It was only when I want back to research this issue of the magazine and refresh my memory that I realised this retrospectively nasty fact.)

At the very top of the top ten list stood four comics that, it was claimed, were the standout issues of 1986 — Watchmen, Love and Rockets, Frank Miller’s run on Daredevil and the number one ranked comic, The Dark Knight Returns.

I pored over the descriptions of these purportedly great comics that had passed me by. I further contemplated the accompanying, mystifying sample panels from each. Panels that, out of context, provided little illumination into why these comics might be so worthy of such acclaim.

The Watchmen panels, for example, showed a man in some kind of body armour talking to another man wearing only underpants. “You’re drifting outta touch, Doc,” said Body Armour Dude. “You’re turning into a flake. God help us all.” Then a second panel of Doctor Mostly Nude Man pondering in thought.

This didn’t particularly sell me on Watchmen. The description didn’t help either: “Enough has been written about Watchmen and Alan Moore that I don’t need to add much to it.”

Gee, thanks Gerard. Really made your case for the book being ranked so highly there.

(Of course, in retrospect, it feels crazy that anybody would need to make a case for Watchmen being a good superhero comic book. But in 1986, those of us who could only afford to dabble at the edges of the industry would have appreciated maybe a bit more of an effort. Throw a few more years on Jones’s jail term for this crime against quality comic book clarity, I say.)

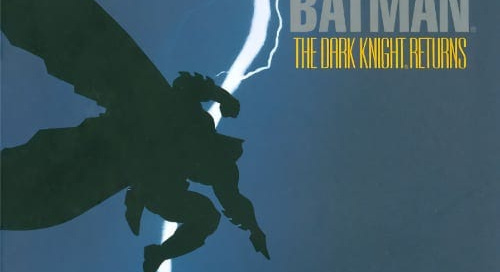

The panels from The Dark Knight Returns, though! These were something else.

As used as I was to the more realistic art of one’s John Byrnes or one’s George Perezes, the far more cartoony style of Miller was startling.

The Batman I knew was a lithe acrobat of a man. Lean. Toned. Liable to do a backflip if a crime-fighting situation called upon it (as it seemed to, with improbable regularity).

Miller’s Batman, in contrast, was a huge, bulging beast of a superhero, one almost incapable of being constrained by the comic book panels in which he was enclosed. A behemoth for whom a backflip was not just out of the question but who looked as if he’d respond to that question by crushing the questioner’s body into a curious pulp.

It was like no Batman I’d ever seen. And the description of the comic sounded like no Batman comic I’d ever read:

“The Joker, a misshapen pustule of evil, breaking his own neck. Superman, a desiccated skeleton in the eye of man’s unleashed power, Batman on a black horse, terror and rage made flesh, a mockery of a hero made heroic by a nauseating mockery of a world.”

Sounded serious to me.

I made a mental note of all the books in the Amazing Heroes top ten list. 1986 wasn’t convenient financially for me to indulge in its greatness. But I wouldn’t always be a poverty-riddled schoolboy.

Just a few years later, for example, I would be a young man in a well-paid job with loads of disposable income, living in the city of Sydney, a city that contained multiple comic books shops for me to visit (most notably, the great King’s Comics). I would visit those various stores at least weekly, disposing of my income on a variety of books.

Eventually, I spotted a trade paperback edition of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns.

I did not hesitate. I bought it and took it home, reading the whole thing in one sitting. The tale was gripping. Set in the near term future (the mid-1990s, presumably), Batman, retired for a decade after the death of Robin, is inspired to return to action as a result of the boredom of waiting for his clunky laptop to install Windows 95.

In the first issue, he fights Two-Face. He scales it up to fight a gang of criminal youths in the second (dang you, criminal youths!). The third issue sees him fighting and killing the Joker (technically, the Joker, crippled at the end of a dramatic chase and fight, breaks his own neck to frame Batman — a classic comedy bit). Then in the fourth and final issue, Bats scales right to the top. He fights Superman himself, dying in the process (or at least faking his own death to get the pigs off his back, man).

This, of course, was yet another change to my pre-Crisis continuity. Before Crisis on Infinite Earths, Superman and Batman were besties. They’d hang out together all the time. Just a couple of bros chillaxing in the Batcave or Fortress of Solitude, calling one another ‘chum’, bonding over being orphans and making fun of Aquaman.

Before the Crisis, nobody questioned this. Supes and Bats were the two oldest and greatest superheroes. Of course they’d be best mates. They’d been sharing a comic book (World’s Finest) since 1941. For four and a half decades, that was all the friendship justification DC’s writers had needed.

It wasn’t enough for Miller. He presented the compelling case that these two foundational heroes of the DC universe would instead almost certainly have fundamentally opposing viewpoints on crime-fighting. So fundamental that they couldn’t possibly be as close as previously portrayed.

Miller’s viewpoint, translated into a colossal climactic battle between the pair, single-handedly redefined their relationship. (Across all media. Without The Dark Knight Returns issue 4, we would never have had, for example, The Great ‘Martha’ Stoush of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Don’t hold that against it.)

Miller’s reimagining of Batman didn’t stop there. For the great power of The Dark Knight Returns was that it forced readers to rethink everything they’d previously taken for granted about young master Wayne.

For the twenty years prior to The Dark Knight Returns, the overwhelming image of Batman in the greater public consciousness was that of comedy genius Adam West delivering ridiculous dialogue with the straightest of all possible faces, BAM!-SOCK!-POW!-ing a celebrity guest’s henchmen, getting captured in an absurd deathtrap at the end of an episode, improbably escaping it at the beginning of the next one, before ZAP!-WHAM!-BLAMM!-ing once more to triumph yet again over the ne’er-do-well villain.

And while I adore West’s Batman, his masterful portrayal made it impossible to take Batman seriously. And comic book fans in 1986 desperately wanted nothing more than that.

‘Why so unserious?’ we shouted as one at the wider, laughing-at-Batman community.

Batman wasn’t a joke. He was a dark character driven by the murder of his parents. A hero trained to the peak of human crime-fighting ability. A fearsome scourge of the criminal underbelly.

But even those of us who felt this way (and to be clear, despite loving West’s portrayal in my more mature years, in 1986 I was definitely among the number who wanted Batman taken more seriously) didn’t really get what a serious version of Batman would look like.

Only Frank Miller truly got that.

Batman was a dark character.

Batman was so dark he spent almost the entirety of The Dark Knight Returns trying to find the perfect death for himself.

Batman was driven by the murder of his parents.

Batman was so driven by their murder that he challenged Superman to fight to the death on the street where they were shot. And as he fought with an actual freakin’ Kryptonian, he monologued to himself about the lessons his parents had taught him ‘… lying on this street… shaking in deep shock… dying for no reason at all…’.

Batman was a hero trained to the peak of human crime-fighting ability.

Batman was an enormous musclebound brute so well-trained that he would, for example, know seven ways to defend himself from a gun being trained on him at point blank range, including three that would disarm with minimal contact, three that would kill and one that would… hurt. (And by ‘hurt’, he meant, uh, ‘cripple’. Ha ha ha! Take that, ya dumb punk.)

Batman was a fearsome scourge of the criminal underbelly.

Batman was so fearsome he would take down a lawless gang of miscreants by challenging the gang’s leader mano a mano in a random Gotham City mud pit and defeating him so brutally that the rest of the gang foreswore all further criminal activity and instead devoted themselves to becoming acolytes of Batman.

The Dark Knight Returns was relentless in this kind of rendering of a ‘more realistic’ Batman. Whatever distance in seriousness 1986 comic book fans felt they’d put between their version of Batman and the Adam West Batman, Miller angrily demanded they add at least that much more again. (And, as mentioned, managed it in a cartoonish art style that paradoxically made the realism even more powerful.)

But Miller didn’t just use The Dark Knight Returns to open comic book fans’ eyes to the brutal reality of what a more serious version of Batman would look like, and how his story might end.

He followed it up with a fresh post-Crisis origin for Batman, Batman: Year One. (This was the one book on the Amazing Heroes list of 25 best comics that I had read, thanks to my ongoing subscription to monthly issues of the Batman book. This meant, of course, that I had at least some exposure to Miller’s Batman even before I caught up with The Dark Knight Returns a few years later.)

It was a one-two punch of superhero character reimagining, surely unmatched in the history of comic books.

Before Miller, the story of how Batman got his name and branding was essentially unchanged since 1939. It was a story that I knew well from The Untold Legend of The Batman. Bruce Wayne relaxing on a chair in his study, pondering how best to combat criminals — renowned for being a cowardly, superstitious lot — spots a bat flit-flit-flitting in through an open window. “A bat!” he thinks to himself. “That’s it! It’s an omen. I shall become a bat!”

Miller’s Batman: Year One version still had a bat coming in through the window to inspire Bruce. But Bruce wasn’t sitting on a comfy chair in his study. He was instead bleeding out after an initial, costumeless foray into crime-fighting had gone awry.

Oh, and the bat? It wasn’t a small flying rodent flit-flit-flitting through an open window. It was a giant, unholy demon-creature crashing through a closed window, spraying glass everywhere.

I shall become a bat, indeed.

Miller had similarly crashed through our understanding of what superhero comics could be. His reimagining of Batman rippled through the entire industry. Along with Watchmen, it ushered in an entire ‘grim and gritty’ era of superhero comics. An era that would wait patiently for me and my disposable income in the early 1990s.

You wanted superheroes to be taken seriously? Here you damn well go.

Next month: The other serious comic book of 1986. Who watches the Watchmen? (Come on. You didn’t really think I was going to skip Watchmen, did you?)