A is for Alien

In which I discuss possibly apocryphal pitches, fiduciary duty, and the art of being pretty fly (for a white guy)

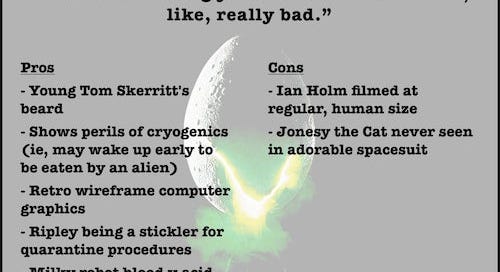

There is a story - perhaps apocryphal - told about James Cameron pitching his idea for the sequel to Alien, the 1979 Ridley Scott movie that grossed $143m worldwide and made superstars out of Sigourney Weaver, a spooky alien monster and the exploding chest of John Hurt.

According to the story, Cameron pitched the sequel in three simple steps. First, he wrote the title of the original movie on a whiteboard. Then he paused a beat before adding an ‘S’ to the end. Then paused a further beat before putting vertical lines through the S so that it read as a dollar sign.

Alien$

It matters not one iota if the story is true. Because it is a perfect encapsulation of the purpose of a sequel. It’s why in this series I intend to explore them and their variants - prequels, franchises and cinematic universes. (Why am I doing so via the almost certainly needless constraint of one per letter of the alphabet? That’s a question that cannot be answered by any of James Cameron’s actions.)

Virtually all sequels are attempts to squeeze money out of a successful predecessor. For this, they are often derided - and most times, rightly so. Many, many (many) sequels are shameless cash grabs with little respect shown to the original source material.

Sequels, however, are required by law to exist. This is not a joke. Publicly listed companies (such as almost all movie studios) have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders. To not maximise revenue from a piece of intellectual property in their possession would be a breach of that duty. If there remains a possibility for officers of those corporations to wring further money from a successful film, they have a legal obligation to do so.

They do not, however, have a legal obligation to ensure that a sequel has anything resembling the quality of the original. Depending on the vision of those signing off on these decisions, they might bow to the demands of short-term cashflow. That is, they’ll immediately squeeze whatever money they can out of an established brand.

More rarely, they take the longer term view: Let’s try to build the brand into something that can provide a recurring cash flow over the long term. Perhaps with related merchandise and other media opportunities.

Either way, though, the final incentive is money.

To be clear, in a publicly listed company, the greenlighting of an original movie is also based on profitability. Sometimes short term (we expect people will like this movie so much we’ll earn more from it than it cost to make). Sometimes long term (an established Hollywood star has a passion project that will almost certainly be a commercial flop, but maybe it will earn critical acclaim and/or endear that star to us in such a way that it makes future successes more likely).

Sequels and other derivative works, however, are more obviously motivated by cash than an original film. There is an established framework of profitability (very few flops are granted sequels). If a sequel can replicate the blueprint of a successful original, it might also replicate its profits.

While this can be a recipe for a quick and easy cash grab, it is also true that much of the best art comes from constraints. There’s no reason the constraints of fitting plot or characters to a pre-existing work (or works) should automatically preclude any of the zillions of aspects that make for a quality film-going experience.

Which brings us back to James Cameron and the sequel to Alien. Cameron had his eye on the dollar sign, but also made one of the most acclaimed sequels in movie history. (Or, in fact, two - because he also gave us The Terminator sequel. But we’ll come back to that later… (or will we? T has some tough competition.))

This is one reason the Alien franchise is the best place to start this A-Z series. (The other reason being that Alien begins with the letter A, long renowned as the alphabet’s first letter.)

The original Alien was a box office hit for 20th Century-Fox. Pitched by writers Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett as ‘Jaws in space’, production was only given the go-ahead in the wake of the phenomenal success of George Lucas’s Star Wars. (Presumably, an idea for a movie that encapsulated the spirit of just one of history’s biggest box office successes was insufficient. But two of them? Well, now you’re talking.)

Director Ridley Scott gave Alien a gritty space-faring vibe similar to Star Wars. Bursting forth from the superficially comparable universe, however, was a horror movie. Not that this was a surprise. The tagline for Alien was the brilliant and sound wave-savvy ‘In space, no one can you scream’. You’d be a damn fool if you went into the film without at least some expectation of horrific, inaudible-scream-worthy, extra-terrestrial monsters.

Alien fulfilled its taglined space horror promise. The lived-in universe that hooked so many Star Wars viewers was dialled up still further. And the glamorous elements of Star Wars were dialled down to zero. No space wizards. No Wookiees. No cute droids. No laser swords or Death Star dogfights or space princesses to rescue.

Instead, we get just a group of blue-collar workers, working for The Company (the unethical corporate employer that lurks unseen behind every film in the franchise). These workers soon stumble onto one of the scariest movie monsters in the history of cinema. A monster that would - in proper horror movie fashion - hunt and kill each member of the crew. One by one, it stalked and devoured them until there was just a lone survivor left (plus a cat). That survivor, of course, was Sigourney Weaver in the role of Ripley.

Ripley would also take centre stage in Cameron’s 1986 sequel, Aliens (to 20th Century-Fox’s eternal shame, they didn’t title it with the dollar sign. Boo! Just come out and say it already).

Much like the titular monster(s), Cameron’s Aliens was the first indicator that the franchise would grow and evolve. The initial face-hugging horror movie that featured a single alien stalking an outmatched space crew was transformed. Now it was a chest-bursting action movie that saw a team of aliens fighting a similarly outmatched team of space marines.

Unlike most action movies of the era, however, Aliens was built around the heroics of a woman (if you can imagine!). Ripley proved herself to be the experienced voice of reason in an overconfident band of testosteronic meatheads. (Even the lady marines were testosteronic meatheads - equality!)

Famously, the franchise embraced a female energy throughout its various entries. Women were consistently the protagonists, and pregnancy themes and allusions abounded. Heck, even the computer was named ‘Mother’. To some extent, this was mere happenstance. The original screenplay didn’t even specify the sex of any of the humans on board the ship. However, once the franchise stumbled onto this theme, it leant into it. Big time.

In Aliens, Ripley embraced her maternal instincts, rescuing Newt, the orphaned daughter of the plot instigators. The big bad of the movie, in turn, was the alien queen, determined to seek revenge against the humans who’d slaughtered her ghastly, deadly offspring. (Fun fact: ‘Ghastly, Deadly Offspring’ was also the title of Rolling Stone magazine’s review of the ‘Pretty Fly (For A White Guy)’ single.)

Aliens proved to be a similar magnitude hit to the original Alien. Pocket change compared to Cameron’s future mind-boggling box office successes, of course, but still above the studio’s expectations. Furthermore, the film didn’t just ensure that the promised dollar signs materialised. Scenes such as Ripley in a mech-suit fighting the alien queen garnered instant action film icon status. They gave the film a degree of critical cachet that would only grow further over the years.

After Aliens, however, the Alien mutations were more hit and miss.

The franchise would continue to rampage over the next three decades (and counting), devouring not just famous and infamous writers and directors, but also other franchises, continuities and genres.

Alien³, released in 1992, saw future hotshot director David Fincher chewed up and spat out by the franchise, causing him to disown the movie. The script for the exponentiated trilogy-closer wasn’t even complete when filming started, but a few key ideas soon emerged. Ripley’s triumphant rescue of Newt from the climax of the beloved previous movie would be immediately undone with the off-screen death (but on-screen autopsy) of her de facto child. In lieu of continuing the relationships established in Aliens, we would instead hang out on a prison planet full of rapists and murderers. Oh, and Ripley would also discover she was carrying an alien queen embryo inside her.

Look, it’s a big swing.

The understandably pro-choice Ripley therefore spends most of the movie trying to abort the new alien queen, ultimately killing herself to do so.

Sigourney Weaver did not escape the franchise quite so easily. For just as The Company puts the financial benefits of controlling and capturing aliens above that of those charged with accomplishing the feat, 20th Century-Fox prioritises the financial benefits of continuing the franchise above whether the actors want to do so.

Not that we should feel too sorry for Sigourney. She was offered $11 million and a co-producer credit to be resurrected in 1997’s conveniently titled Alien: Resurrection. This time, the franchise hungered for director Jean-Pierre Jeunet and screenwriter Joss Whedon. Both of them would, however, improbably escape this bonkers, dissonant mess more or less unscathed, retreating to the relative safety of directing Amélie and show-running the Buffy the Vampire Slayer television show, respectively.

Having carelessly missed out on the opportunity to destroy Whedon, the Alien franchise instead now turned its sights to an even more toxically masculine science fiction monster of the era. A movie so masculine it generated the most masculine meme of masculine masculinity ever captured in masculine meme form - a pair of musclebound soldiers (Arnold Schwarzenegger and Carl Weathers), whose absurd macho handshake soon devolves into a bicep-bulging, arm wrestling match.

The Predator was a douchebag alien visiting Earth on a hunting expedition. (More on Predator later… (maybe. The P’s are pretty packed too.)) Armed with technology far beyond ours, it would hunt down and kill primitive humans. Or at least that was the plan. Instead, the Predator would invariably stumble at the last step, like a big game hunter being satisfyingly gored to death by a rampaging elephant.

(Of course, those were the movies we here on Earth were allowed to see, and you’re crazy if you think they weren’t being filtered for a Terran audience. No doubt out there in the great big galaxy, most of the predators were successfully getting their jollies from hunting down hapless humans.)

In an inspired piece of intellectual property crossover, instigated by those mad geniuses over at Dark Horse Comics, these toxically masculine predators got to face the feminine energy of the aliens from the Alien franchise in a pair of Alien vs. Predator movies in 2004 and 2007.

After two classic ‘Predators are from Mars/Aliens are from Venus’ crossovers, we ended with a tie, before both franchises separated, injured badly… perhaps fatally.

Predator was not, however, the only franchise touched by Alien. Ridley Scott later revealed that he considered the universe of Alien to be a future version of the Blade Runner universe. James Cameron was also tempted to place a piece of Terminator technology in there. Did all these things reconcile? Of course not. But the Alien franchise didn’t concern itself with anything so tedious as a lack of continuity.

Until suddenly, it did. Because just when we thought the Alien franchise was dead, it returned. This time it had in its sights screenwriter Damon Lindelof - a television show-runner reeling from the negative backlash of the final season of Lost.

If Lindelof thought 2012’s stealth Alien prequel Prometheus would offer a haven from the reception for the Lost finale, he was mistaken. Reviewers panned Lindelof’s screenplay for Prometheus, calling it weak, confusing, and, in the case of part-time movie critic James Cameron, one that ‘didn’t add up logically’. On the plus side, nobody mistakenly thought the characters were dead the entire time. Little victories.

The movie itself, however, garnered positive reviews, thanks to the direction of the true hero of the franchise, the one who’d been there at the very beginning. Ridley Scott was back, out of hibernation, stripped down to his underwear, and he would take no more guff from the Alien franchise.

Scott also directed the sixth (the AvP movies are considered out-of-continuity side quests) regular instalment in the Alien franchise. That was 2017’s magnificent Alien: Covenant, which picked up plot threads left over from Prometheus and tied together various pieces of dangling logic. The result was a consistent timeline for the entire franchise. One that gave the aliens an origin story (including a reminder that you can’t spell ‘Alien’ without ‘AI’), a dark, full-circle conclusion, and a viable reason for hating Guy Pearce.

The marauding Alien franchise had at last been brought under control by the man who’d first confronted it.

But that’s just boring old storytelling and universe building and internal consistency.

The Company has no interest in any of that. (To be fair, neither did audiences, apparently. Alien: Covenant was a box office disappointment.)

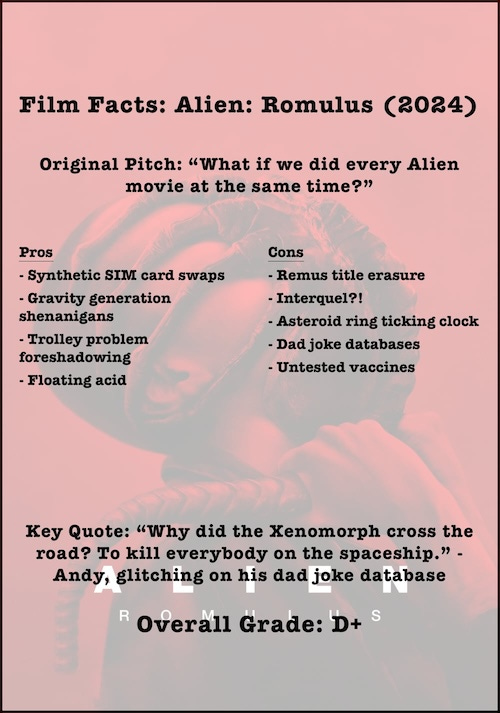

In 2024, then, Alien: Romulus saw a group of scavengers poking through the debris of seemingly abandoned space vehicles, hoping to find sufficient life support to escape to a new future.

But enough about director Fede Álvarez and co-writer Rodo Sayagues, and their tendency to just throw random aspects of all previous entries of the series into a screenwriting Vitamix to see what will happen. (At one point, this film’s resident synthetic undergoes an intelligence upgrade. Sadly, the movie never does the same.)

The plot of Alien: Romulus, as derivative (and eventually outright bonkers) as it is, isn’t the point. The point is whether the franchise can still be milked for both future movies and television series.

We wait patiently for The Company’s further analysis.

— Return to The Master List

If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy my weird combination memoir/history of superhero comic book series. Or you might not. Only one way to find out, though.

A Lifetime of Superhero Comics — Introduction

I have spent virtually my entire life reading superhero comic books. Now that’s obviously not true. I don’t spend every waking hour reading superhero comics. Even at the peak of my interest in comic books, I was never quite that obsessive. But from a very young age — as far back as I can remember — I would spend my pocket money on comic b…