J is for Jaws

In which I discuss one-fourteenth of a movie career, the power of parody, and meta-case cowardice

Previously:

Before we see a single frame of footage of Jaws (1975), we hear the two notes of John Williams’ score that are the film’s most famous byproduct.

The notes are, fittingly enough, down deep. If not below the sea, then, at least, below middle C. An E played in unison on the bassoon, double bassoon, cello and double bass, followed by those same instruments moving a half-note higher to F.

Even if you don’t know any music theory and wouldn’t know a bass clef from a giant seabass, you know the notes. Even if you haven’t seen Jaws, you know the notes. You can hum them.

And even if you have minimal familiarity with musicology, marine biology and movie history, you know what those two notes signify.

Danger.

Williams is the greatest film composer in history, nominated for 54 Academy Awards. He created some of the most beloved movie scores and themes of all time - Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, to choose a random five year stretch of his seventy year career.

But the two-note motif for Jaws is arguably Williams’ greatest compositional trick. So simple was it that director Steven Spielberg, who had teamed up with Williams for his feature film directorial debut, The Sugarland Express a year earlier, thought at first it was a joke.

It was no joke, and a good thing too. Because Williams’ variations on that basic motif created a theme so ominous and menacing that it more than compensated for the fact that we don’t see the shark until an hour and 21 minutes into the film, when it pops its head out of the ocean to terrify Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) throwing churn off the deck of the Orca, the boat of veteran shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw).

The reason for such a delayed entrance, famously, is that the shark (nicknamed ‘Bruce’, after, oh, let’s say, Bruce Springsteen) was born not to run. No, not in the ‘aha, it was born to swim’ sense. More in the ‘oh, why won’t this fucking stupid mechanical fucking shark ever fucking work fucking properly?!’ sense.

The malfunctioning mechanical sharks (there were three Bruces and two Orcas - a little bit of movie magic for you!) and a myriad of other problems associated with shooting on the open sea meant that expenses for the film more than doubled, from the budgeted $4 million to $9 million. As mentioned, it was only Spielberg’s second feature film, and while he’d shot a similarly themed television movie (Duel, in which an enormous truck threatens normal everyday people) and several television shows (including, famously, the pilot of Columbo - “Oh, just one more thing about these attacks, Mr Shark, if you don't mind me asking? I can't help but notice those powerful jaws of yours. Seems to me they could take an awfully big bite out of a young lady swimming under the moonlight. You can imagine, can’t you? Somebody with powerful jaws getting hungry, seeing a tasty human skinny-dipping, taking a little chomp. Anyway, sorry to bother you, Mr Shark. Carry on, carry on.”), it’s hardly surprising that the complexities of the Jaws shoot might have had a young director feeling… well, out of his depth.

Except this is Spielberg, right? One of the great movie-makers. So he nimbly worked his way around the various problems. He and credited screenwriter Carl Gottlieb used the delays to rewrite scenes just prior to shooting them, injecting character and levity into the original screenplay from Peter Benchley, writer of the novel upon which the film was based.

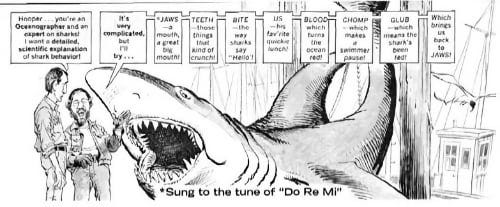

The flakey shark? Moved mostly off-screen, making it approximately nine thousand times more terrifying. An unseen force pulling Chrissie under the water in the opening scene. The Kintner boy’s blood-geysering raft that triggers the chilling dolly zoom reaction shot. A collapsing jetty, a fin poking out of the water, a flurry of yellow barrels. All augmented by shark POV shots and the Williams theme.

By the time you reach the shark’s first proper on-screen appearance, more than half the movie is gone and you didn’t even notice. Jaws is a film that races along, particularly in its first half where Brody deals with the initial attacks and futilely tries to get the mayor to close down the beaches.

The pace becomes more leisurely in the back half as Brody, Quint and Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) head out to sea to confront the beast, old school style (like, Beowulf levels of old school). Spielberg takes time to deepen the characterisation of the three men, to showcase their histories, their motivations, and their willingness to sing sea shanties or request larger sea vessels.

By the time we enter the final Boss battle (reverting to our earlier theory that the shark was named after Springsteen), we know how each of them will try to defeat the creature. Hooper will try to beat it with science, Quint with gripping, drunken Indianapolis monologues. Both will fail. Instead, it’s Brody who finishes the shark off, perched atop the last remnants of the ship, shooting Chekhov’s compressed air tank and blowing the beast into a billion pieces.

Look, it’s a bloody good movie. And, in the summer of 1975, it captured the imagination of filmgoers like nothing before. Naturally, this made it a target for parody.

The fourth episode of the hip new comedy show Saturday Night Live featured a sketch about the Land Shark, voiced by Chevy Chase, knocking on doors, pretending to be (among other things) a Candygram delivery boy, in order to be invited inside, where he could devour his prey.

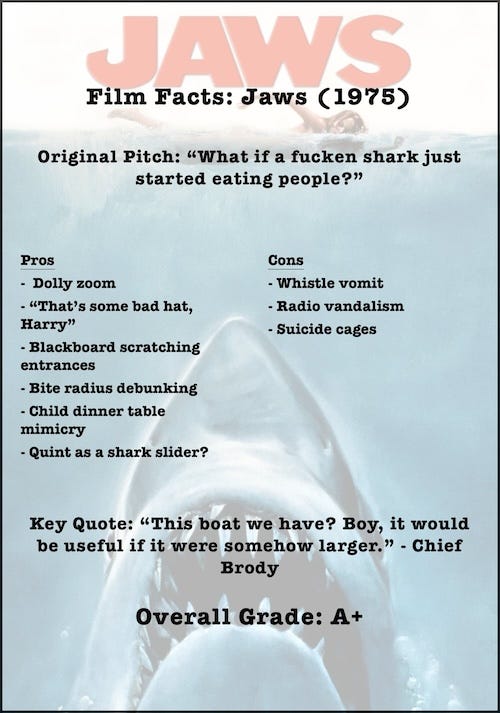

MAD magazine had not just its mandatory parody (‘Jaw’d’) of the film in issue 180 in January, 1976, but also two issues later included it as one of three films (alongside The Godfather and The Towering Inferno) that it believed should be remade as musicals. Retitled ‘The Shark and I’, the musical version memorably1 featured Hooper’s sung explanation of shark behaviour to the tune of ‘Do Re Mi’.

JAWS - a mouth, a great big mouth

TEETH - those things that kind of crunch

BITE - the way sharks say ‘Hello’

US - his fav’rite quickie lunch

BLOOD - which turns the ocean red

CHOMP - which makes a swimmer pause

GLUB - which means the shark’s been fed

Which brings us back to JAWS!

Perhaps most famously, in 1980, Airplane! (or Flying High! as it’s inexplicably known in Australia) opened its relentless joke machine onslaught of a film with a Jaws parody, the tail of the plane poking above the clouds as Williams’ theme plays, before it roars out and into the opening credits.

In addition to being a cultural phenomenon, Jaws was also a box office phenomenon.

It opened to a record weekend at the US box office and just kept growing, number one for fourteen consecutive weeks, eventually overtaking The Godfather to become the highest-grossing film of all time, in the process more or less inventing the concept of the summer blockbuster.

When it opened internationally later in the year, it replicated that success worldwide, grossing $132 million worldwide on initial release. The $5 million it had gone over budget was forgotten and forgiven.

Jaws is, in every sense, a masterpiece, but it was also a highly profitable masterpiece.

Naturally, then, the studio demanded a sequel.

Spielberg wasn’t on board to direct the sequel. Although, having said that, there’s a case to be made that Jurassic Park (1993) is a sequel of sorts to Jaws. A Spielberg-directed action-adventure thriller based on a best-selling novel, centred on a tourist attraction threatened by human-devouring monsters, where the real enemy may be the greed of the people in charge? It’s not too dissimilar, right? (It’s certainly more similar than Spielberg’s other 1993 movie, Schindler’s List.) J is also for Jurassic Park, and if I were a braver writer, I might have tried to make the meta-case of the latter J franchise being a sequel to the earlier one. I am not, however, that braver writer.

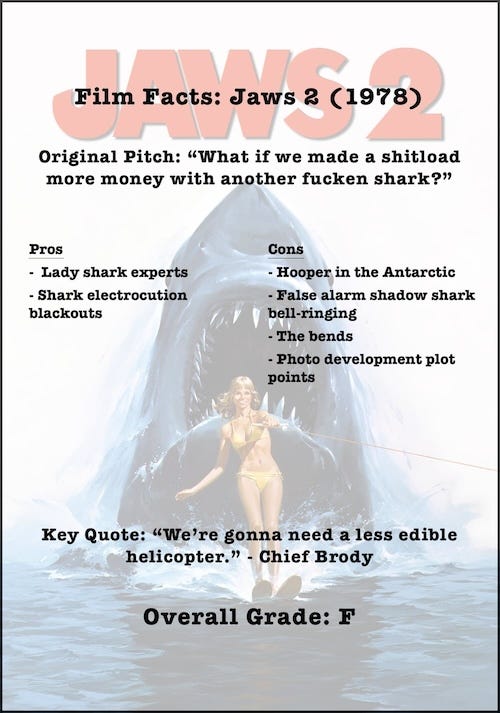

Instead, let’s take a look at Jaws 2. This first sequel, released just three years later, kept a few of the key elements of the original. Carl Gottlieb was back to write (or at least co-write) the screenplay. John Williams once again scored the film. Roy Scheider returned as Chief Brody, as did Lorraine Gary as his wife Ellen Brody.

And, infamously, as pointed out by Twitter user Adam Goodell (@adamgoodell), ‘The mayor from Jaws is still the mayor in Jaws 2. It is so important to vote in your local elections.’

The sequel was also boosted by one of the great movie taglines. ‘Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the water…’

Unfortunately, despite retaining some of the key elements that made the original such a brilliant film, a fatal error had been made.

In Jaws, the shark was a force of nature. There was nothing personal in its attacks. It was hungry. It found itself in human-infested waters. It ate some of those humans. Who among us can honestly say that under the same circumstances, they wouldn’t do the same?

Brody, Quint and Hooper went after the shark. It didn’t come for them.

In Jaws 2, the shark comes across more as a serial killer in a slasher movie (perhaps picking up on something in the zeitgeist - Halloween also came out in 1978 and Friday the 13th would follow in 1980). No longer a mindless sea creature, it instead goes out of its way to intelligently attack and kill people.

The malevolent shark photobombs scuba divers, stalks and devours water-skiers and, in one magnificently stupid scene near the end of the movie, eats a helicopter that arrives to rescue a bunch of dumb, horny teens.

Because, hey, what’s a slasher movie without dumb, horny teens? Jaws 2 provides an absolute smorgasbord of them, including Brody’s only-slightly-older-than-strict-chronology-from-the-first-film-would-suggest children, joining the rest of their partying peers on a sailing soiree despite their father having (literally) grounded them.

The shark devours enough of the stupid adolescents to satiate the audience. But, alas, not itself, opening it to the possibility of being tricked into biting into an electrical cable and frying itself from the inside out.

Despite Jaws 2’s flaws, it, too, broke box office records, briefly becoming the highest-grossing sequel in history. (Rocky II came for it the following year, decisively wielding the power of titular Roman Numerals to take the crown.)

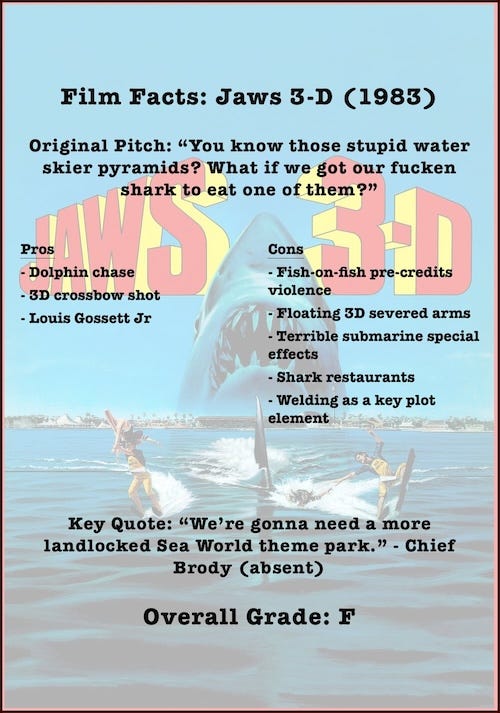

So, of course, we got Jaws 3 in 1983. Or, leaning into a timeless cinema gimmick, Jaws 3-D (in 1983D). We’ve somehow time-jumped seventeen years since the first movie (a fact that perhaps comes as no surprise to one of the actors, future Back to the Future franchise star, Lea Thompson in her first feature film) and are focusing on the two youngest members of the Brody Bunch, Mike and Sean, as they deal with yet another goddamn shark.

Mike, now played by a cocaine-addled Dennis Quaid, works at a Sea World. Annoyingly, it’s a Sea World into which a giant great white shark has snuck. Also sneaking in? His brother Sean, the only sane member of the Brody family, who understandably refuses to go into the water under any circumstances whatsoever.

Unless, that is, a scantily clad Lea Thompson asks him nicely. Look, the woman’s about to date Howard the Duck and her own son. Sean Brody’s not going to provide much of a challenge.

The point is, the shark rampages around Sea World for the longest 98 minutes of your life, tediously terrorising and eating theme park visitors (more Jurassic Park foreshadowing!) in 3-D, until a combination of trained dolphins, a conveniently swallowed hand grenade, genuinely dreadful rear projection and Manimal star Simon MacCorkindale defeat it.

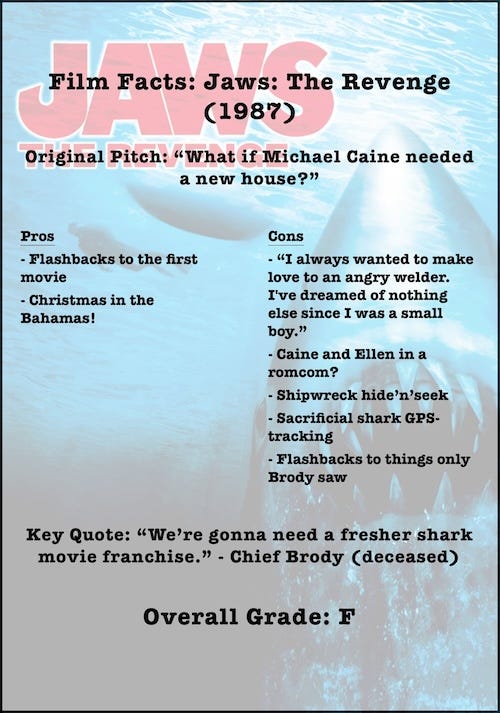

Jaws: The Revenge (1987), the fourth movie in the series, is often credited as the worst one. And, make no mistake, it’s abysmal. Michael Caine, shoehorned in as the widowed Ellen Brody’s new love interest, infamously claimed: “I have never seen it, but by all accounts it is terrible. However, I have seen the house that it built, and it is terrific!”

However, as idiotic as Jaws: The Revenge is (eg, the shark inexplicably pursuing the surviving Brodys from Amity to the Bahamas, sidekick characters returning to life after being eaten, and the shark reacting to a climactic boat spearing by, uh, exploding), it does have one advantage over the third instalment.

Namely, it brought the sequels to a close.

The shark had been milked dry (if you can forgive one of the more malformed marine monster mistaken for mammal metaphors ever written).

Other shark or shark-variant movies would periodically pop up. Deep Blue Sea. Sharknado. The Meg. The Suicide Squad. Under Paris. But after Jaws: The Revenge, we were done with the Jaws franchise.

Jaws was the first summer blockbuster. Over the course of three sequels, it then laid out the classic pattern that almost all future franchises would follow. Something fresh and exciting, capturing the imagination of filmgoers, before each subsequent instalment steadily stripped away everything interesting about it.

For Jaws, specifically, the minimalistic John Williams two note theme that opened the first movie - the one that so sublimely warned that there was danger looming - had been replaced by something completely one-note.

That monotony (in both senses of the word) would serve as its own warning for future movie franchises.

— Return to The Master List

If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy my weird combination memoir/history of superhero comic book series. Or you might not. Only one way to find out, though.

‘Memorably’ in the most literal sense, in that this article (and this song parody in particular) is my earliest memory of MAD magazine, sneaking off during a party at one of my parents’ friends’ home, stumbling on this issue and devouring it. Despite not understanding, well, pretty much anything, I loved it, and went on to write for MAD magazine myself for two decades