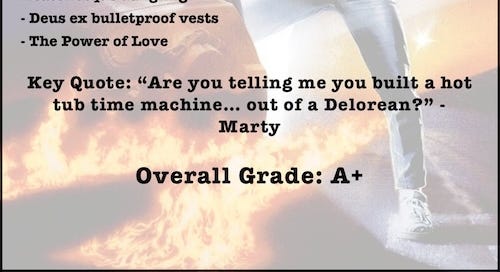

B is for Back to the Future

In which I discuss rhyming musician names, sitcom trope metaphors and muddled time travel rules

Previously:

The perfect sequel, from the profit-seeking studio’s viewpoint, balances familiarity and novelty. It should resemble the original enough to please the audience in the same way, eliciting similar box office success. It should also, however, include enough new elements to trick moviegoers into feeling as if it’s worth spending their money all over again.

The brilliant trick of the first Back to the Future sequel is that the time travel element at the core of the franchise allows them to pull the ultimate version of this ‘give the audience the original movie, just slightly different’ trick. Because, after a visit to both the far-flung future of 2015 and a dystopian alternate version of 1985, the final act of 1989’s Back To The Future Part II gives us a delightful do-over of the final act of the original Back to the Future. You want the original movie? Here it is. But now it also has a bonus second version of Marty and Doc traipsing secretly through its climax.

(There had been a glimpse of this revisiting trick in the first movie when Marty went back ten minutes early (ten minutes, Marty? ten minutes?? come on, man) to see himself be chased into the past by the Libyans, but the sequel went to town with it.)

Same, but different.

I’m getting ahead of myself, though. Let’s go back. Back to Back To The Future, the original movie from 1985.

Back To The Future, written by Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis (the Bobs) and directed by Zemeckis, was a simple tale of time travel, terrorism and potential incest. Teen slacker Marty McFly accidentally finds himself trapped thirty years in the past where he needs to perform an emergency Oedipusectomy, getting his horny adolescent mother, Lorraine, to turn her gaze from him to his socially awkward father, George, so that he can use a chronologically precise lightning strike to return him to the present day (as 1985 was controversially known at the time) without his existence being wiped from the timeline.

It’s a basic plot that has all kinds of conflict and turns built into it. A fine foundation for a film, upon which the Bobs built an (appropriately) clockwork screenplay. One that pushed all those conflicts and threats to the limit, expertly raising the stakes for Marty at every turn, while adding audience-satisfying extras in the form of jokes, action sequences and Huey Lewis cameos.

The Bobs were in complete agreement that there was only one actor for the role of Marty - Michael J Fox, the breakout star of Family Ties, the popular 80s television sitcom that dared to ask the question ‘what if a teenager was a capitalist?’.

After all, a comedy movie built around time needed a star with the best comic timing, and nobody in 1985 had better comic timing than Michael J Fox. Even better, the Bobs had a connection to their prospective lead. The producer of Back To The Future, a Mr Steven Spielberg of Hollywood, California, was a friend and neighbour of Gary David Goldberg, the producer of Family Ties. (Spielberg had been one of the first to see a rough cut of the Family Ties pilot, so was well aware of Fox’s comic capabilities.) When Spielberg asked Goldberg about Fox’s availability for Back To The Future, however, he was told in no uncertain terms that there was no way the schedules could possibly be made to work. (Fox’s comic timing on a quip by quip basis was great, but on a more macro level, perhaps left something to be desired.)

Disappointed, the Bobs reconvened and were soon in complete agreement that there was only one other actor for the role of Marty - Eric Stoltz, the breakout star of Mask, the popular 1985 movie that dared to ask the question ‘what if a decade from now, this movie will be forever overshadowed in the public consciousness by Jim Carrey’s The Mask?’.

(The Stoltz suggestion in fact came from Sid Sheinberg (the head of Universal at the time), a man with many strong, and wrong, opinions about Back To The Future. One such opinion was infamously that the movie should be called Spaceman From Pluto. (This is not a joke.))

The Stoltz suggestion soon proved to be almost as wrongheaded as the Spaceman From Pluto title, although it took six weeks for the director to be sure of it. That’s when a desperate Zemeckis consulted with Spielberg, showing him some early cut together footage, and the pair agreed that Stoltz’s performance wasn’t working in the film.

Spielberg spoke to Goldberg again, and, this time, a compromise was struck. Back To The Future could have Fox, as long as his work on the movie didn’t interfere with his Family Ties duties.

Fox leapt at the opportunity. He’d heard all about the movie through Crispin Glover (George McFly), with whom he’d previously worked on both season two, episode eleven of Family Ties (‘Birthday Boy’) and 1983’s TV movie High School USA (a TV movie in the truest sense, with stars of Facts of Life, Lost in Space, Gilligan’s Island, and Diff’rent Strokes (x2) all joining Fox for teenage shenanigans).

And so, in scenes reminiscent of a classic sitcom trope (including, for example, an episode of Family Ties itself - season two, episode eighteen, ‘Double Date’), Fox spent eighteen-hour days scurrying back and forth between his two dates, the flashy and gorgeous Hollywood movie and the less traditionally beautiful (but still quite cute in a ‘show next door’ way) TV sitcom, trying to give full attention to both.

Unlike the inevitable result of the classic sitcom trope, however, Fox succeeded in his big screen/small screen double date antics. Succeeded wildly.

Family Ties went from strength to strength in its third season, and Fox’s role as Alex P Keaton grew in prominence. The following year he won his first Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series (for the season four premiere episode, ‘The Real Thing’, in which he met his on-screen girlfriend and future real-life wife, Ellen (Tracy Pollan)).

(Fun fact: The character of Doc Emmett Brown was originally known as ‘Emmy’ Brown in reference to Christopher Lloyd’s pair of ‘Outstanding Supporting Actor In A Comedy Series’ Emmys for Taxi in 1982 and 1983. Would Marty have also been renamed Emmett in the sequels, had this original screenplay nickname stuck? Answer: contractually, yes.)

Of course, Fox’s Emmy claims in 1986 were also helped by him now being a bona fide movie star, after Back To The Future dominated the 1985 box office, earning almost $400 million to become the highest grossing film in the world that year.

For, as it turned out, virtually everything about Back To The Future worked. The DeLorean. The hand-wavy time travel rules. The book tie-in (honestly, one of the single funniest, laugh out loud things I’ve ever read is Ryan North’s B^F, his recap of the Back To The Future novelisation - I cannot recommend this highly enough). The instantly iconic Alan Silvestri score. Einstein. Strickland. Variable numbers of pine trees. Everything.

Including one of the great comedy movie casts.

Lloyd’s Doc Brown provided a crazed, cartoon vibe, ‘Great Scott’ing up a (lightning) storm, mispronouncing gigawatts, and apologising for the ‘crudity’ of incredibly elaborate models of Hill Valley.

Lea Thomson’s Lorraine radiated forbidden sexual attraction to ‘Calvin Klein’, just enough to give the movie a deliberate controversial edge to skate(board) around. (Zemeckis: Ultimately, that’s what made the movie successful, because it was a little bit edgy but it was done in a fun way. Spielberg: It kind of made my skin crawl.)

Thomas F Wilson’s Biff was a constant looming threat, but one sufficiently comically lunkheaded and ultimately emasculated that the (less deliberate) controversial edge of his attempted sexual assault could just about be waxed over.

Glover’s George summoned his own magnificent, off-kilter energy, with nervous, soft-spoken line deliveries and stilted chuckling, earnestly declaring Lorraine to be his ‘density’, before supplying the climactic punch that simultaneously resolved roughly half a dozen different plot lines of the script.

Add to the mix Fox’s boyishly charismatic chemistry with each of them, and of course you have the biggest movie of the year. One that raced to 88mph and allowed us to see some serious(ly funny) shit. One that made everybody forget about the Stoltz misstep at the beginning of shooting.

But not quite forget about it, right? Because anybody with even a passing knowledge of Back To The Future lore knows about the Stoltz version of Marty. Because, sure, while lots of movies have different actors who were considered, approached, or even auditioned, for key roles, it’s much less usual for one of those actors to then spend six weeks shooting the film, as Stoltz did.

Six weeks of shooting is enough to make it incredibly easy to imagine a timeline in which Zemeckis persevered with Stoltz. So easy, in fact, that 2023’s DC cinematic multiversal, time travel entry, The Flash, used the Stoltz Back To The Future variant as a shorthand indicator that The Flash was now in a parallel reality. (I have lots of thoughts on The Flash which I’ll save for whenever I get around to the DC cinematic universe, which, I’m telling you now, probably won’t be the D entry.)

In our universe, of course, the Fox variant of Back To The Future had overwritten the Stoltz version. And once the Bobs got the hang of replacing inconvenient timelines, they went to town with it.

Because it wasn’t just Stoltz being replaced by Fox in the role of Marty McFly. Fox’s voice in the ‘Johnny B Goode’ scene at the ‘Enchantment Under The Sea’ dance at the end of the movie, for example, was also replaced. This time with the voice of somebody who could actually sing, Mark Campbell of the R&B band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack (one of the great rhyming band names, alongside Milli Vanilli, Tears for Fears and Shania Twainia).

And when the film was released on VHS in May, 1986, the last scene of the movie, a throwaway gag in which Doc Brown, Marty and Jennifer fly off in the upgraded DeLorean, had also been overwritten. This time, quite literally overwritten, with the words ‘To Be Continued’ overlaid, the joke ending now upgraded to a genuine teaser for a future sequel.

After all, you don’t have a hit as big as Back To The Future without studio pressure for a sequel. Especially when you’ve already teased the premise for that sequel, jokingly or otherwise, at the very end of the first movie.

Which brings us back to where I started this piece. Zemeckis spotted the potential for the ultimate piece of sequel ‘same, but different’ing, revisiting the climax of the original movie a second time, and that became the cornerstone of Back To The Future Part II.

With Zemeckis off making Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (starring Christopher Lloyd, who somehow out-cartooned a plethora of actual animated characters in his role as the villainous Judge Doom), however, Gale was left to write the sequel mostly alone. He got so carried away with the task that the sequel ballooned in size to two sequels. Two sequels that would be shot back-to-back and released back-to-back in 1989 and 1990.

The first sequel, Back To The Future Part II continued the exploration of overwriting timelines within the story. At the end of the first movie, George’s punch of Biff changed the 1985 timeline to which Marty returned, with George now a successful (and, more importantly, from a mid-1980s perspective, wealthy) science fiction writer. Sure, Marty was now trapped in an alien family (not literally alien - the timeline wasn’t changed that much) who shared memories and lives to which he was no longer privy. On the other hand, he had a cool truck, so didn’t seem to care too much.

(The rules of time travel in the original Back To The Future are somewhat muddled. Sometimes the film suggests Marty’s presence bootstrapped events. For example, Mayor Goldie Wilson had been mayor in 1985 at the start of the movie, and Chuck Berry was presumably also already an established rock’n’roll pioneer, yet both were, according to the movie’s lore, inspired into those roles by Marty himself, which meant Marty had, in some sense, always existed in that week in 1955. Other times, however, Marty’s actions changed the timeline that existed at the beginning of the movie. Most notably, when he saves George from being struck by Lorraine’s father’s car (worth it, however, if only for the underrated, exasperated line, ‘Another one of these damn kids jumped in front of my car.’), thus triggering much of the plot of the movie. But if Marty’s changing timelines, then, in some sense, this must be the first time he’s been back in 1955. Confusing.)

In Back To The Future Part II, however, the franchise abandons the bootstrapping version of time travel and leans directly into the concept of timelines being overwritten. It also makes the overwriting of timelines far more threatening. Biff’s overtly Trumpian dystopia in the middle act shows the perils of changing the past in a way that had only been partially glimpsed in the original. (Yes, Marty had the ongoing threat of his entire existence being overwritten in the original movie, but that was a personal timeline threat rather than the more global threat of the Billionaire Biff timeline.)

More interesting than the timeline overwriting of the plot, though, is the external timeline overwriting. The Fox-replaces-Stoltz style overwriting. Because Back To The Future Part II leans heavily (“Why are things so heavy in the future? Is there a problem with the Earth's gravitational pull?”) into that. (And, yes, a lot of this is merely recasting, which can happen in any movie franchise, but it’s more fun to view it through the same lens as the movie’s plot. Humour me, people.)

First, there’s yet another overwriting of the ‘where we’re going, we don’t need roads’ scene, this time with Elisabeth Shue replacing Claudia Wells in the Jennifer role. (Not that it really matters who is in this role - as minor a character as Jennifer was in the first movie, she’s somehow even more minor in the sequels. Also, she spends most of the sequels unconscious, with Gale taking the least imaginative possible option for dealing with the plot inconvenience of her being in the car at the end of the first movie. )

More controversially, Crispin Glover, a polarising figure during the first movie, was replaced by Jeffrey Weissman for Back To The Future Part II. Weissman did his best George McFly impression, obscured by such tricks as ‘being upside down’ in a scene, and augmented by snippets of footage of Glover in the role from the first movie. Glover was not happy with this overwriting of the timeline, though (and in particular, the lack of publicity about the replacement, which suggested to him that the Bobs didn’t want the audience to know there was a new actor in the role (Weissman himself apparently initially thought he was being hired as Glover’s double)). Glover was so unhappy that he eventually sued for the misappropriation of his likeness. His argument was that the prosthetics and mimicry used by Weissman was a deliberate violation of his intellectual property. The counterargument from the Bobs, Spielberg and co was that Weissman was continuing the portrayal of George McFly, not Glover. Nevertheless, they settled out of court. (Can overwritten timelines be sued out of existence? It’s certainly a plot twist worth pursuing in some future time travel franchise.)

It’s not just actor timeline rewrites coming to the fore in Back To The Future Part II, either. Marty’s character is also heavily rewritten in the sequels. A clunky (and/or clucky) ‘don’t call me chicken’ character flaw is shoehorned in from a less interesting screenwriting timeline in order to provide lazy motivation for Marty to do stupid things.

A lot of sloppy writing can be forgiven, however, when a movie gives us that transcendent third act, complete with the perfect button of Doc Brown dancing a happy jig from the end of the 1955 portion of the first movie before being interrupted one second later by the returning Marty from the end of the 1955 portion of the second movie.

That’s a superb piece of cinematic sleight of hand, in a film that offers us perhaps another way of thinking about a sequel. A successful sequel is, in its own way, an alternate version of the original. Same, but different.

As Doc faints in cartoon exasperation at the situation, we realise we can’t stay mad at you, Back To The Future Part II. For all your flaws, you’re a successful sequel.

But can we stay mad at Back To The Future Part III? Sure, we can. Because the third film drifts too far away from the original, getting bogged down in not just a tedious Western, but also a love story for Doc Brown, and needless Jules Verne references, none of which we signed up for when we saw the first movie. (Why did they make us sign for that first one, anyway? Is the contract legally binding? Let’s get Crispin Glover’s lawyer on the case.)

Sure, there are some running gags from the original sprinkled over the third film to give us a taste of that Back To The Future goodness (and some great new gags too. I am inordinately fond of the exchange “Listen, you got a back door to this place?” “Yeah, it’s in the back.”) But the clunkier character bits from the second film also get a sprinkling, and that’s no good for anybody. Plus, at no point do we get the Uncle Joey ‘get out of jail free’ card of literally revisiting the first movie. So, yeah. Back To The Future Part III is a big, sloppy miss.

On the plus side, though, there’s a kickass flying train at the end. So maybe I’m being too harsh?

More importantly, while both sequels were profitable, the Bobs have to date resisted the urge to add any further movies to the franchise, showing a level of restraint rarely seen in Hollywood.

A legitimately great movie with one inspired sequel, and then an abandonment of the franchise after a clunky conclusion to the trilogy?

Look, I’ve seen worse timelines.

— Return to The Master List

If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy my weird combination memoir/history of superhero comic book series. Or you might not. Only one way to find out, though.